Amistad: Cinque's Slave Rebelion Arrives in Montauk

On August 26, 1839, six men in a rowboat came through the surf at Montauk looking for food and water and to find out where they were. They were a strange sight. Four were black men in rags, carrying machetes. The other two were white Cuban merchants, in civilian clothes that had also turned to rags. They were prisoners of the black men, accompanying their captors to shore to hopefully find out where they were. The shoreline was supposed to be Africa. This was not Africa.

Had they ever found anyone to talk to—they never did as far as anyone knows—it would have been a strange conversation. The Africans spoke several different languages, including Mende, which were unique to their homeland in the newly founded West African nation of Sierra Leone. The merchants spoke only Spanish. And whomever they met would be local East Hampton farmers tending their cattle, off in Montauk to pasture until September. They spoke English.

Behind them just offshore was the two-masted schooner they had rowed from. It had been at sea for two months, having left Havana, Cuba on what was supposed to be a three-day journey to Puerto Principe. After so much time at sea, it too was a wreck. On board were 53 African slaves—49 men and four children—who had fought and overwhelmed their captors, and a cabin boy, another slave, but a Spanish-speaking one from Cuba. They were all hoping there would soon be more food and water. This was a very desperate situation.

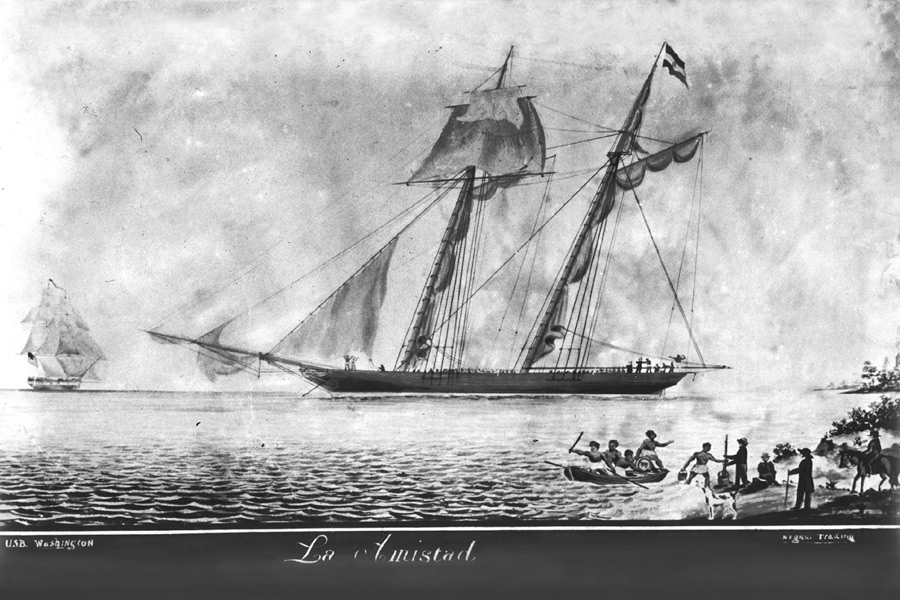

An encounter did occur. A U.S. Navy survey ship, the Washington, with armed sailors on board, rounded Montauk Lighthouse, came upon the ship and boarded it. The men who rowed ashore—as well as those still onboard the Amistad—were captured, and the Navy towed the ship to New London, Connecticut to turn the whole thing over to the authorities. Along the way in, the Africans staged a rebellion against these new captors, but that failed. In New London, the authorities, at the urging of the two Spanish merchants, arrested the blacks as pirates, murderers and revolted slaves and took them to prison in New Haven. The Spaniards also demanded that these 53 slaves, property they owned, be returned to them.

Thus began an encounter between the world of African natives and the community of the United States. The encounter was to last two years. And it would galvanize the nation.

The man who organized the slave revolt at sea was a powerful African man in his mid-20s who called himself Sengbe Pieh, but who had, in Cuba, been given the Spanish name of Cinque.

Cinque, weeks later when a translator was found, explained himself. He was born and raised in Mani, a village in what is now Sierra Leone. He was the son of the leader of the Mende tribe residing there. And it was expected he would take over from his father some day. Cinque said he was kidnapped into slavery when a man he owed money to became impatient. Members of the Ley tribe did the deed. He was then sold to a chief who sold him to a Portuguese slaver, who took him to Lomboko, where he was chained up with several hundred other black men and women of various African tribes and placed in a lying-down position in the hold of a large ship that sailed them to the Americas.

The ship was the Tecora. The place they were taken to was Havana. And there, in an auction, he and 52 of the others were sold to two businessmen, Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montes. These businessmen took these slaves to a smaller ship, a schooner called the Amistad (Friendship). Again put below decks in chains, they were intended to be taken to Puerta Principe to be sold to a sugar cane farmer there. They never made it.

Bad weather delayed this passage. It was supposed to be two to three days. But when they still had not arrived after four, the captain of this ship ordered those on board to go on half provisions. With that, an altercation took place—the slaves were shackled, so this was no big problem—between some crew members and some Africans. The crew members flogged a few of them, and then told them, according to Cinque, that they would be killed and eaten on arrival at Puerta Principe. Cinque decided that if it were at all possible, he and the others would take over the ship.

The moment came. The slaves were brought on deck in groups to eat. When it came Cinque’s turn, he saw and was able to grab a loose nail near to where he sat. That night, he used this nail to unlock his shackles and then, silently, the shackles of the others. Below decks they now looked for weapons, and soon found a barrel full of cane machete knives. They waited, and at dawn, they struck.

The captain of the ship fought the takeover and Cinque killed him. The cook was also killed. The two crew members fled toward shore in one of the two skiffs on board. Cinque was now captain of the Amistad, and he had Montes and Ruiz prisoner. He instructed them to steer the ship toward the rising sun back to Africa. They did as they were told. But they tricked him. By day, the ship sailed east, but at night, without the sun as a guide, they steered north and west. It was on this zigzag course that, eventually, they approached the shore, not of Africa, but of Montauk.

After being thrown in jail in New Haven to face charges of piracy and murder, they were arraigned in the morning. As no interpreter had been found at this point, none of them could have any idea what was happening. Cinque was only able to express his desire to go back home.

At this time, the United States had already voted to make slavery illegal, although the states in the South had their own laws. Slavery also was illegal in Great Britain, Spain and the Netherlands, although not seriously enforced.

In Washington, the Spanish Ambassador demanded that President Martin Van Buren turn over the Africans to the Spanish government to be tried under Spanish law. Van Buren was not one of our stronger presidents. Fearful of the southern states whose voters were pro-slavery, he agreed to do that.

This was now a major national news story, however, and Van Buren’s decision never went into effect. Lawyers for the Africans pointed out that with the charges against them, this was now a matter for the courts. A judge would decide. Still, nobody could understand the language the Africans spoke.

And then, forged documents were found. Ruiz and Montes had created documents that gave these Africans new Spanish names and said these 53 black people from Africa were not from Africa at all, but were what were called “black Latinos,” experienced Cuban slaves who already knew Spanish. They would be worth much more as that. This was a fraud these two were going to perpetrate on the buyers.

The lawyers for the Africans now argued that these men, now with these new identities, had never been properly enslaved. They should be set free.

Financing this legal defense was Lewis Tappan, a merchant, Simeon S. Jocelyn, a Congregational minister, and the Reverend Joshua Leavitt, the publisher of an abolitionist newspaper. Then, suddenly, someone found an interpreter. And now the Africans could understand what was going on, and they could speak for themselves.

As a result of all this, the judge, in the district court in Hartford, ruled for the Africans and ordered them returned to Africa.

President Van Buren, however, would have none of it. He ordered the decision appealed to the Supreme Court. As a result, Tappan tried to enlist a prominent Boston lawyer to take the case. But none would. And then he remembered former president, John Quincy Adams, now retired in Boston. Adams had offered his services for the first trial, but Tappan, noting that Adams had not been a strong abolitionist in his time, turned him down. Now, with the case going to the Supreme Court, he asked Adams to step in, and Adams did.

All this was taking time. The Supreme Court would not hear the case until February 1841, more than a year after the Africans had been charged. In the meantime, Cinque and the others, with their interpreter, were becoming something of a tourist attraction. They were put on display. People came from everywhere to see them and talk to them. One of them, I have learned, was a phrenologist, someone who examines people’s heads and supposedly comes up with their personality traits.

Here is the phrenologist’s report about Cinque:

“Cinque appears to be about 26 years of age, powerful frame, bilious and sanguine temperament, bilious predominating. (Following this is a long passage about the physical dimensions of Cinque’s head.) The head is well formed and such as a phrenologist admires. The coronal region being the largest, the frontal and occipital nearly balanced, and the basilar moderate. In fact, such an African head is seldom to be seen, and doubtless in other circumstances would have been an honor to his race.”

The phrenologist’s report concludes that Cinque’s strongest traits were firmness, self-esteem and hope. Also strong were benevolence, veneration, conscientiousness, approbativeness, wonder, concentrativeness, inhabitiveness, comparison and form. On the other hand, mirthfulness was below average.

Here’s something that Lewis Tappan wrote after visiting Cinque in the prison.

“He is with several savage-looking fellows, black and white, who are in jail on various charges. Visitors are not allowed to enter this stronghold of the jail, and the inmates can only be seen and conversed with through the aperature of the door. Towards evening, we made a visit to Shidquau (sic) and conversed with him a considerable time. He drew his hand across his throat, as his roommates said he had done frequently before, and asked whether the people here intended to kill him. He was assured that probably no harm would happen to him—that we were his friends—and that he would be sent across the ocean towards the rising sun, home to his friends. His countenance immediately lost the anxious and distressed expression it had before, and beamed with joy. He says he was born about two days traveling from the ocean; that he purchased some goods and being able to pay for only two-thirds of the amount, he was seized by the traders, his own countrymen, and sold to King Sharka for the remaining third.”

John Quincy Adams, now 73 years old, appeared before the Supreme Court for two days. His testimony took eight hours. He did not argue the issue of slavery. He argued the issue involving the rights and liberties of American citizens. It was about Habeus Corpus. How could a free man—they had never been enslaved—be handed over to a foreign government this way? Where was the ‘blessing of freedom’ provided for in the Constitution? The Supreme Court voted 8 to 1 to uphold the decision to release the Africans.

(Interestingly, the court did not rule that the Cuban deck boy slave be freed. He had become a slave fair and square. Abolitionists hustled this boy off to New York City to freedom, however.)

But still the Africans could not be sent off. The President of the United States was now John Tyler, a Virginia planter and slave owner. He refused to provide any American warship to take the men home.

Eventually, money was raised privately, and the 35 surviving Africans were transported back to Sierra Leone accompanied by Christian missionaries, who soon set up a missionary in Sierra Leone. Cinque found no trace of his family or his home and assumed they had all been either killed or sold into slavery. He then disappeared into the bush for a while, breaking off with the missionaries. When he was in his mid-60s, however, ill and infirm, he returned to the mission and asked to be buried upon his demise in the Christian cemetery there. And that’s where he lies today.

Between Cinque’s return and his passing, rumors circulated here in America that he had become a slave trader himself, but no evidence of this has ever been put forward. These rumors could be attributed to slave owners.

Last month, the City of New Haven, along with several other organizations, including Yale University and the Albert Schweitzer Institute at Quinnipiac, announced that they were raising $100,000 to provide four vans of medical supplies, protective clothing and other things needed to the officials of Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone to fight the Ebola virus that is devastating that country. New Haven and Freetown became sister cities in 1997. Also during that decade, the entire cabinet of the Sierra Leonean government came to New Haven to attend the dedication of a statue of Sengbe Pieh, as his name is now spelled, which graces the town green of New Haven.

Anyone interested in aiding this medical effort—this is probably the first city to city aid effort for Ebola—should contact New Haven Mayor Toni Harp. Perhaps East Hampton Town might like to contribute.

This is the true story of Cinque and the Amistad as it is known today. And there are other local connections. President John Tyler, the bachelor Virginia plantation owner, was to become the only sitting President ever married while in the White House. His bride was 21-year-old Julia Gardiner, the daughter of a U.S. Senator, who lived in Manhattan and

East Hampton.

And 15 years ago, Steven Spielberg of East Hampton, captivated by the story of Cinque, made a splendid motion picture about it called Amistad. It was nominated for four Oscars—including one for supporting actor Anthony Hopkins. But it won none.