Talking with Dan's Papers Cover Artist Mym Tuma

“It’s what I’m all about,” says East Moriches painter and sculptor Mym Tuma, who is about to mail a copy of her small picture book of images, drawings, poetry and short stories (“Talking Goose” and “Talking Swan”), published late last year.

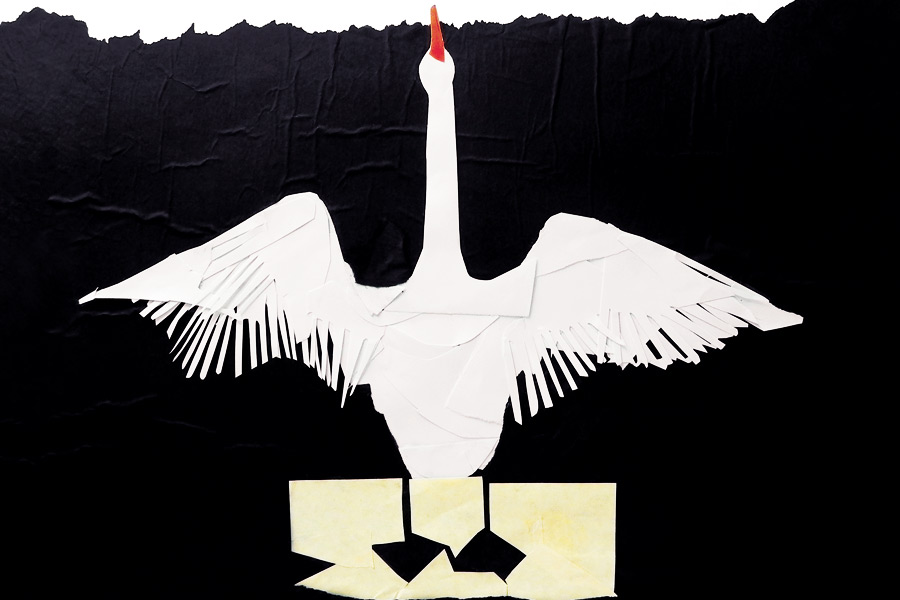

Called The Anatidae: Mute Swan and Geese Paper Collages (Come to Life Graphics), the eclectic collection “written and photographed on the East End of Long Island,” is exemplary, not only of Tuma’s work these days as an artist and writer but also welcoming of words and images by others who are also paying tribute to the natural world. Tuma, an activist on behalf of ducks, geese and especially swans who have been visiting her doorstep for the last few years in East Moriches, notes that these birds have deeply affected her work, not to mention her heart.

Egrets also get a shout out in the booklet, as she celebrates their “spindly black legs” on bodies that remind her of “an amphora vase with an extended thin neck.” She’s delighted, of course, with the recent turn of events whereby the Department of Environmental Conservation announced revised plans for the mute swans of Long Island; the focus will now be on devising policies and strategies to contain, not kill, them. Though well known for incorporating oceanic and coastal materials into her work, including beach pebbles, sand, sprouting seeds, spiraling shell forms and working with pastel, epoxy, acrylic and fiberglass, Tuma has also had a long-time passion for cutting swan-part shapes out of colored paper and designing striking, elegant, minimalist collages she calls “sculpted paintings,” as evidenced on this week’s cover.

What is the special attraction of mute swans, geese and ducks, and why did you choose to do them as painted collages?

I see in these migratory birds not only intrinsic, graceful beauty—their curvature, their flying off and returning—but metaphors for “the independent life and as symbols of fertility.” As I say in The Anatidae, “the use of the hard edge, the simple form and the linear, rather than the painterly, approach is intended to emphasize two-dimensionality and to allow the viewer an immediate, purely visual response.” Collage captures a bird’s spontaneous movement.

The Anatidae contains a short essay, “The Origins of My Art in the Environment,” where you talk about how you always loved to travel, kind of roughing it, drawing, painting, sculpting, responding to “the energy of shorelines.” You landed on the East End shore in 1991. What attracted you to this area?

Being located by the sea at the edge of the land is a metaphor for my mind’s eye. The harmony, the serenity of the place, encourage the creative life and overcoming hard times and obstacles.

You began your painting career in earnest in the ’60s in a studio in the remote village of Lake Chapala, in southern Mexico, a place whose “vibrant colors and forms of energy” inspired organic principles that would inform all your work. Some of it—sensuous flowers, cabbage heads, ovular-shaped abstract forms—has led admirers to compare you to Georgia O’Keeffe. Are there deeper reasons for the comparison?

As I say in O’Keefe and Me, the correspondence that grew up between Georgia O’Keeffe and me continued for a decade. I may have been naïve in seeking out a veteran artist and asking for her help to launch new work. The openness and directness of my untutored approach so astonished O’Keeffe that she took me under her wing and I became a protégé of sorts…no one else was direct enough to say to O’Keeffe, “I understand what you’re doing because I understand what I’m doing.”

Mym Tuma’s work can be seen at the Wildlife Refuge in Quogue and, this Saturday afternoon, May 16, at Walden Pond in East Moriches.