The Extraordinary Cartwright Island

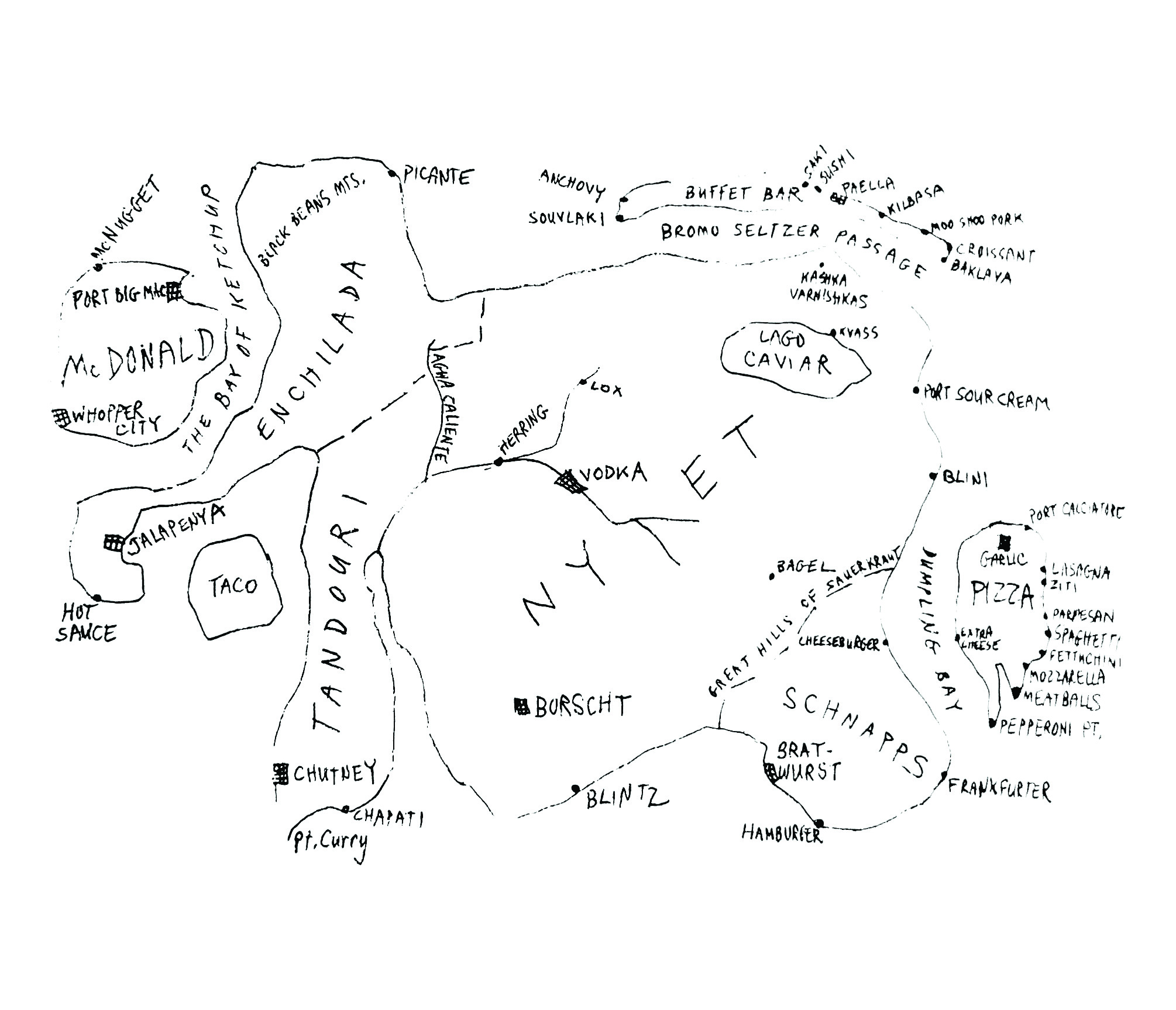

When the great glacier rumbled down from the North Pole 21,000 years ago, it came to a halt just south of Connecticut, then retreated, leaving big and little dirt and rock islands.

The largest of them is Long Island. The smallest, Cartwright Island, just a humble half acre of uninhabited dunes, beach grass, sand and boulders. Yet there’s an extraordinary history. Humans just won’t leave it alone.

Cartwright Island was noted on maps the Dutch explorer Adriaen Block drew when he explored this area in 1611. It is located one mile north of what is today Amagansett, and two miles south of Gardiners Island, a private island five square miles in size.

Cartwright was included as part of Gardiners Island in 1639 when the Montauk Indian Chief Wyandanch gifted it to Lion Gardiner for several trinkets and coats.

Shortly after that, the King of England approved the Gardiner purchase. He declared Gardiner to be its owner as a “proprietor,” a designation giving Lion Gardiner the same rights governors of other colonies were given. An early descendant of Lion Gardiner, for example, hung one of his farm workers after he convicted him of murdering another worker.

As for Cartwright Island, the deed from the King gave its metes and bounds as part of the sale, including, it was said, the water around Cartwright for “as far as an ox can wade without getting its belly wet.”

Through the years, the proprietors of Gardiners Island had lookouts who escorted people off their big island if the visitors they arrived unannounced or without a reason.

But Cartwright suffered no such rules. People held picnics on it, camped overnight on it, fished from it over the years, welcome to it, as the Gardiner family said.

During the 1950s and 1960s, well-known artists and painters, particularly abstract expressionists, began showing their work at various galleries in the nearby Hamptons on Long Island. “Fridays at Five” became a social occasion at these galleries.

And then, over Labor Day Weekend in 1969, a Friday art gallery opening was held on Cartwright Island, and was unlike any other. It came about because 40 days earlier, two sculptors, Ronnie de Rosa of Manhattan, a commercial artist and Bob Dhaemers, a professor of Art at Mills College, spent the night in tents on Cartwright Island with their wives and children. The moon shone down. Two American astronauts earlier that afternoon had just landed on it and for the first time were walking on it. It inspired the artists. As a result, the two decided to build a giant sculpture on Cartwright Island.

They returned a few days later with steel panels and blowtorches and 40 days later Lunar Suite 1, a soaring piece of stainless steel, was introduced to the world on “Friday at Five” on Sept. 1, 1969 on Cartwright. This was one of the greatest art gallery openings of all time. Hundreds of people attended, including this reporter. A band played, wine flowed, food and speeches were given. Late in the party, a Piper Cub began to circle Cartwright. “Hey,” someone shouted. “Get back from the beach. He’s coming in.” The beach was only 50 yards long. It was impossible, but as people got out of the way, he did it anyway, coming to a halt and emerging from the plane with two friends to be toasted with champagne. What a memorable occasion.

The sculpture remained up for years and years. A group called the Barnes Landing Association, whose members looked out over the bay, said the sculpture spoiled the view. And then, at some point, it was gone, although I don’t know how that came about.

In 1973, a man died in a boating accident at Cartwright and it made national news. He was David Rumbough, the grown son of actress Dina Merrill who lived in East Hampton. Off for a ride in a 27-foot speedboat owned by his friend Jonathan Keith, the boat hit boulders guarding the west side of Cartwright at high speed. Rumbough died. Keith survived.

Several years later, perhaps as a result of this, the state of New York passed laws that allowed the state to take over Cartwright and other small islands, now considered shoals rather than islands, to adorn them with lights and reflectors so mariners would better know of their locations.

In 1996, the owner of the Island at that time, Robert David Lion Gardiner, “the 16th Lord of the Manor” as he called himself, tried to adopt any stranger with that last name who’d be willing to take over Gardiners Island. He was approaching 90 but had failed to produce an heir. No one took him up on it, however, and so when he died, the island fell into the hands of his niece, Alexandra Creel Goelet of New York City. Her husband, Robert Guestier Goelet was a wealthy New Yorker. But now, no Gardiner owned Gardiners Island.

In 2018, Roderic Richardson, who earlier on had camped out on Cartwright Island with his wife, came out on a small sailboat and, upon landing there, was confronted by security guards who had seen them from two miles away on Gardiners Island. There were now “No Trespassing” signs on Cartwright.

We live in litigious times.

An argument ensued. Richardson was asked to leave. He would not leave. And with that, he pulled up two “No Trespassing” signs and threw them into the bay. The East Hampton Town Marine Patrol was called and in the end, Richardson was charged with third-degree criminal tampering and trespassing. But Richardson was a fighter. In court, he produced a document showing that the state had taken control of Cartwright. Meanwhile, the Creels declared that they owned it and could prove it with the provision about the ox. But the judge, Steven Tekulsky, was not impressed by the ox. In the end he said it was unclear who owned the island, and as a result, he dismissed the case.

How did Cartwright Island get its name? It was originally called Ram Island, but in 1930, a Long Island historian named Morton Pennypacker found documents showing that in the 1880s Cartwright was named after Frederick Cartwright and his son Clifford Cartwright. During the 19th century the father sailed an open boat from Sag Harbor to Honolulu and the son at another time lost his life saving the lives of the crew of the sinking freighter Ida Belle. After Pennypacker died, his papers were given to the East Hampton Library’s historic collection.

That’s some of the history of Cartwright Island.