Tohanash Tarrant: 10,000 Years and Counting

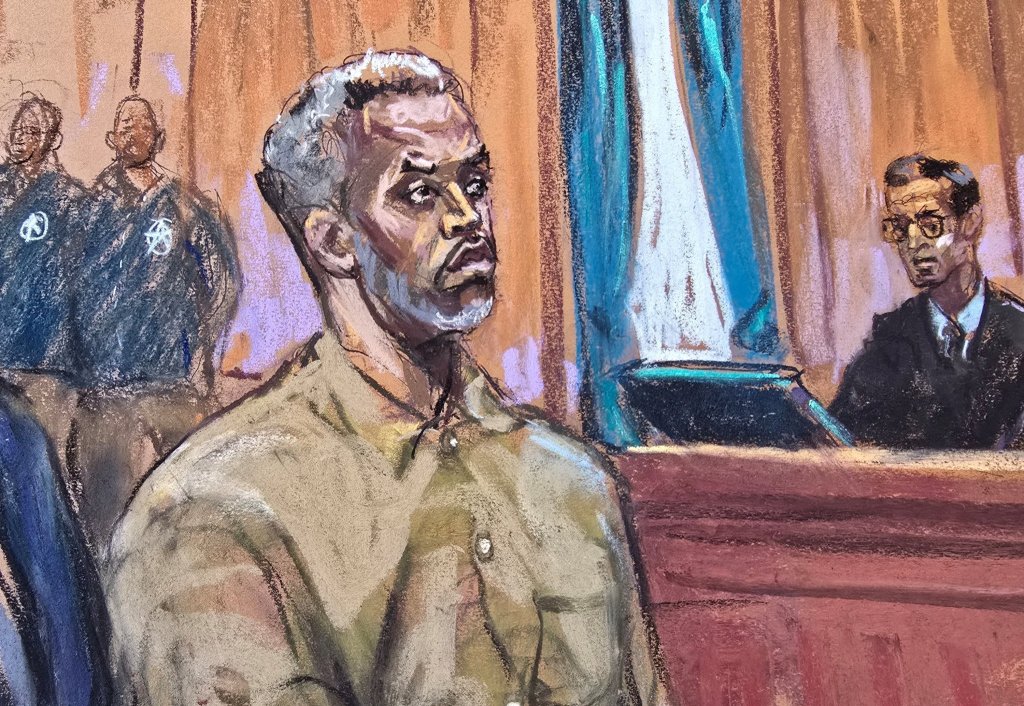

James Keith Phillips won the first Dan’s Papers prize for nonfiction with his entry “Magic Shirts” last year. Phillips, a member of the Shinnecock Nation, wrote about his ceremonial beaded shirt. He talked about its magic—now meet Tohanash Tarrant, the artist who beaded it.

Tarrant, whose mother is Shinnecock and father Hopi/HoChunk, wears many hats at the Shinnecock Nation Cultural Center and Museum—office manager/administrative assistant, crafts artist, tour guide, newsletter editor and proud all-around resource. A ceremonial dancer since the age of five, she does beading for the regalia worn by powwow dancers. Some of her work is on display at the museum, including baby moccasins made with beads stained a slight purple and barrettes made with sweet grass, found in abundance before the “contact.” That’s the word Native Americans use to refer to the arrival of whites on their shores.

For sure, contact changed the Shinnecock way of life, “a history that goes back 10,000 years when our people inhabited this area.” It’s a history that is largely erased for many Americans, even for the descendants of the original Nation. The mission of the cultural center and museum is to educate the public, including those who live on or near the Southampton reservation. Central in this effort, Tarrant says, will be the Wikun Good Gathering Place & Living History Village, which will open on Memorial Day 2013. Its significance, she adds, is that “our people will tell our story.”

The museum (David Martine, director), established in 2001 on Shinnecock property, is a separate entity from the reservation. It is “the only Native American-owned and operated, nongovernmental, not-for-profit” organization on Long Island “dedicated to honoring the Ancestors and living history.” The exhibits at the museum span various time periods. Many of the displays have to do with hunting and fishing, but there are bronze sculptures, paintings and murals depicting the history as well.

The Shinnecocks traveled in the region, intermarrying with other tribes and ethnic groups, but they kept their ceremonial traditions. Tarrant’s wampum jewelry exemplifies their distinctive history. Wampum, she notes, does not mean money, though it is commonly defined that way because wampum was used by Europeans in barter and trade. For the indigenous Eastern Woodlands people, wampum had significance as sacred shell beads used in rites. Replicas, such as the shell ornaments Tarrant makes, reflect the coloration of clam and whelk shells, which had different hues due to different mineral content in the water. Lore has it that the word itself, “wampum,” is a shortening of an earlier word “wampumpeag,” which derives from Narragansett, meaning “white shell beads.”

Tarrant speaks of wampum as “the life giver” because shellfish were a big part of the ancient Native American diet. She smiles—she’s still learning her own history. Myths persist, she says, such as the claim that because some Shinnecock “don’t look Indian,” they’re not. Her reply? “You can’t have someone else tell you who you are.”

A volunteer at the cultural center for years, Tarrant knows her way around the East End, having gone to school here. But she has also traveled to Central America as part of LIU Global (formerly Friends World Program). Politically minded, she focused her studies on indigenous communities and came to appreciate how art and craft were at the center of cultural inquiry. The colors and patterns of a Shinnecock headband, for example—arrows in a sunburst design that is gradually sequenced—are symbolic of sunrise and sunset. Of course, genes will out: Tarrant comes from an artistic family of painters, glass blowers, welders, weavers—her great grandmother Edith Thunderbird, the wife of Chief Thunderbird, did superb loom work. Tarrant, always encouraged to pursue the arts, is now encouraging her own two children to do the same.