ART WALK: Seen and Overheard at the Outsider Art Fair

Passing from the crisp geometry of a wide Chelsea street into the glut of paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media works that filled the Metropolitan Pavilion earlier this month, I experienced sensory overload, similar to entering an antique store or thrift shop.

The 33rd annual Outsider Art Fair was surprisingly cohesive in its tried-and-true entropic state. As my eyes adjusted to the mayhem, I couldn’t decide if the complete disregard for curation was refreshing or distracting.

Approaching the booth of Progressive Artist Studio Collective (PASC), which was presenting with New York’s Shelter Gallery, I found myself face-to-face with joyful skeletons swathed in red cloth, communing beneath a crescent moon, and wide-eyed visages outlined in thick black, white, and pink brushstrokes. Upon closer inspection, I learned that PASC aids artists with disabilities and/or mental health differences in developing independent artistic practices.

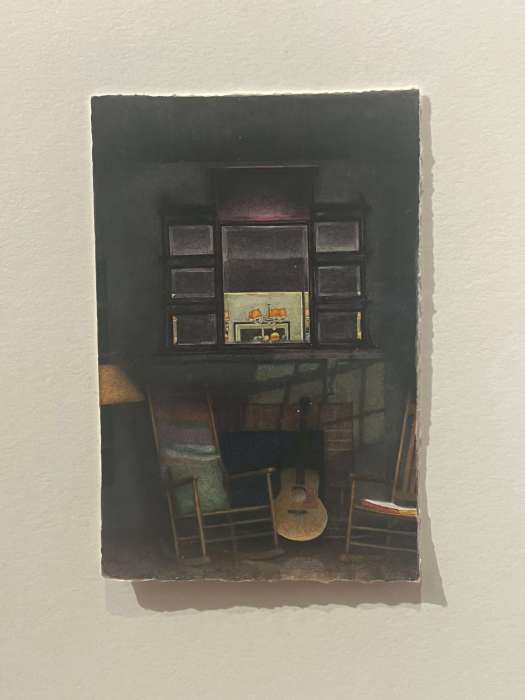

As I wound my way through the jumble of booths, I realized with a slight pang of guilt that I was subconsciously trying to discern the “real” outsiders from the kitschy imitators. My guilt was slightly alleviated when I overheard a fair worker singing the praises of Charlie Ritchie, whose drawings and watercolors of domestic spaces were on view at BravinLee Programs’ booth. Ritchie, he explained, was a retired Metropolitan Museum of Art curator. “Not technically an outsider,” he admitted, “but it’s an outsider vibe.”

But what constitutes an “outsider vibe”?

As I traversed the pavilion a second and third time, distinct patterns emerged. There were hieroglyphs, totems, masks, exotic creatures, and cartoonish monsters. Crayons, acrylic paint, pipe cleaners, clay, and cardboard sprung up at every turn.

The term “outsider artist,” often associated with “self-taught” or “naïve” artists, typically encompasses three overarching categories, the terms and composition of which are themselves highly contested: folk art, usually handmade and rooted in the traditions and aesthetics of a particular culture; “primitive” or “exotic” art, a derogatory classification of non-Western art; and art created by those considered mentally ill or disabled. As I circled the fair, I kept returning to an observation made by Donald Kuspit in an Artforum review of the show Outsiders: Art Beyond the Norms at Rosa Esman Gallery that I recently read:

There is something of Post-Modernist melancholy in the institutional situation of outsider art—which is, after all, art that we think of as made by people who are or ought to be institutionalized.

What place does outsider art hold in a landscape of decaying institutions and frenzied pathologization?

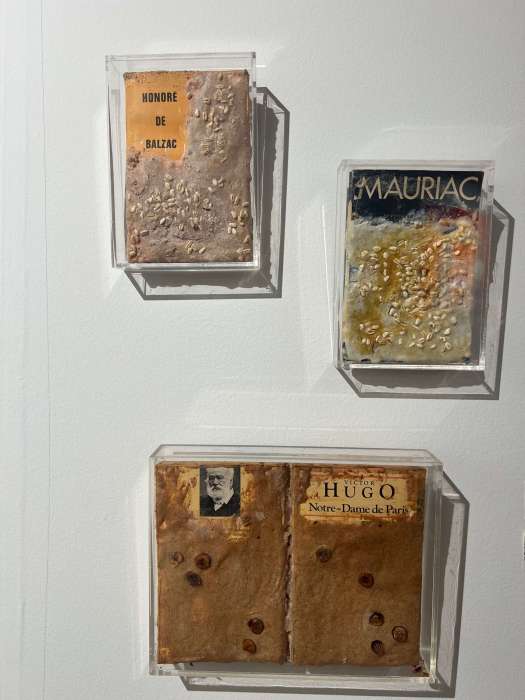

I found respite in the works that appeared to have been neither created nor chosen with the aim to fulfill viewers’ preconceived notions of “outsider art.” In a sea of artistic presentations clamoring to be extraordinary, Denise Aubertin’s “cooked books” at Galerie Kahn stood out as delightfully bizarre and charmingly deadpan. There’s something about art that can laugh at itself and also at you, the viewer, that restores my faith that the avant-garde spirit didn’t die with Duchamp.

Three battered—in both senses of the word—books by Victor Hugo, François Mauriac, and Honoré de Balzac awkwardly perch on the wall. Aubertin (1933–2019), who created her first “cooked book” in 1974, described the project as “An act of derision, of subversion, but also a desire to create an unusual and marvelous object.” Smothered in flour paste embedded with grains and nuts, these peculiar objects hover ambivalently on the fringes of collage and sculpture, conceptual art, and the gleeful antics of restless kids let loose in the kitchen on a rainy day.

Kriss Munsya’s photograph even caught my eye from across the room—no small feat amid a throng of six-eyed demons and clashing Crayola hues. Two figures—one fully clothed, turned toward the camera with their face masked in a disco ball-like mosaic of mirrored tiles, the other shirtless, back to the camera with their head turned to the left and eyes cast downward—stand rooted in a lush field of untamed grasses. Gangly palm trees tower watchfully over them, their sharp fronds reaching upward in stark relief against the luxurious blue of the sky.

In both medium and style, even is a stark deviation from the familiar tropes of “outsider art.” The image is strikingly aware of its own magnificence, defying the stereotype of the unselfconscious outsider artist who creates art purely for its own sake, lacking ambition or technical skill.

“I went to art school, but I’m pretty much self-taught,” I overheard an artist sheepishly divulge to a potential collector as I headed toward the exit.

As I left the pavilion, it struck me what was most unnerving about the category of “outsider” that this year’s iteration of the fair obligingly fulfills: the artwork brought into the world of “outsiders” by art world insiders exudes unawareness or complacency. These structures shut them out in the first place. Few works were overtly political, feminist, or queer. Perhaps it’s a mark of the generation of art history discourse in which I came of age, but categorization and curation devoid of institutional critique feel—ironically—naïve.

What criteria render some outsider art worthy of insiders’ and collectors’ attention? And how could a presentation of outsider art avoid falling into the trap of fetishization?

This year’s OAF seems to suggest that the answer to the first question is its fulfillment of our vision of “outsider,” which comforts us that we are, in fact, inside. The work allows us to peer into the minds of the insane and the exotic landscapes of the Other without leaving the comfort of our own viewership.

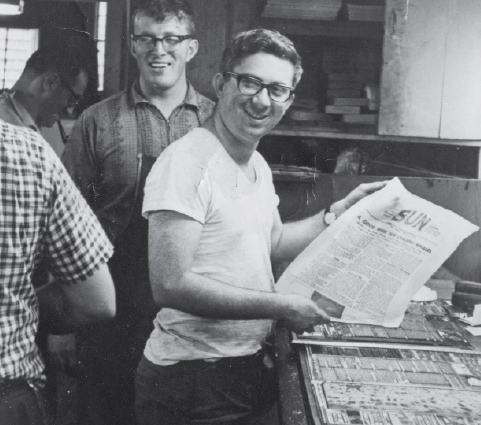

As I pondered the second question, my thoughts wandered to Documenta, an art fair of sorts that takes place every two years in Kassel, Germany. Initially conceived in 1955 as an effort to spotlight art deemed degenerate by the Nazis, Documenta is, by definition, intensely aware of its own cultural/political circumstances. Each Documenta coheres around a predesignated concept—for instance, the theme of Documenta 15 in 2022 was “lumbung,” the Indonesian term for a communal rice barn. Organized by Jakarta-based artist collective Ruangrupa in close collaboration with 14 other collectives and D15’s 1500 participants, the self-sustaining micro-universe went beyond the wall-and pedestal-based artworks, comprising a communal kitchen, artist dormitory, free press, daycare, skateboard park, and more.

What would an outsider art fair put on by outsiders, brought together to celebrate and question their own outsiderness, look like? There’s only one way to find out, but I imagine there to be cooked books of all genres, in every language, for every dietary need.