Hope and Light: Magne Furuholmen's Jazz-Lit Pilgrimage at National Arts Club

Where are certain artists who carry the unbearable elegance of paradox — musician and painter, architect of pop melodies and architect of form, public icon and private contemplative. The creator of this week’s Dan’s Papers cover, Magne Furuholmen is one such artist, a man who has moved through the corridors of fame with the cool poise of a European prince, only to reveal — quietly, insistently — that his true ambition lies not in celebrity but in legacy.

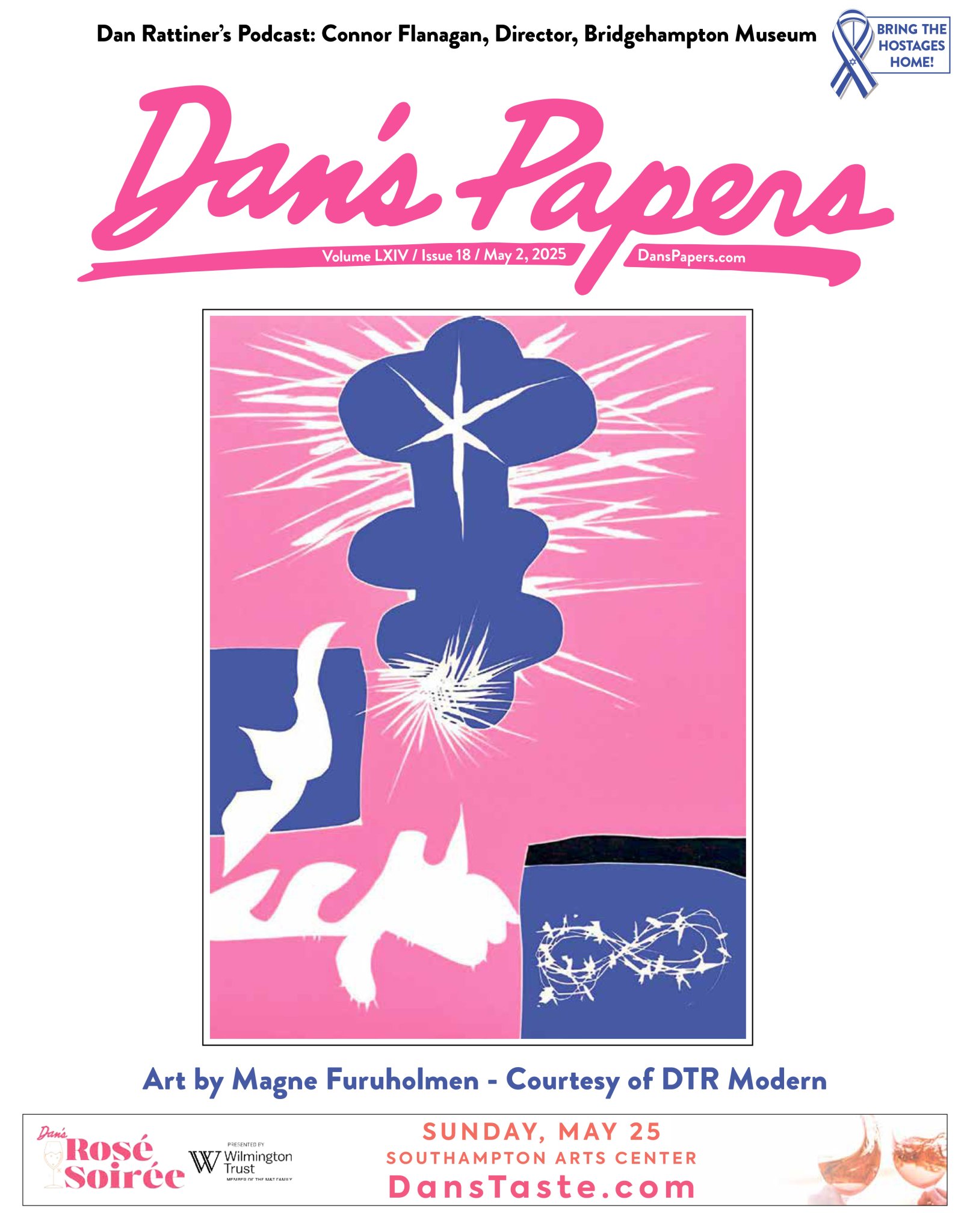

This spring, at the storied National Arts Club in New York, Furuholmen unveils Esper Lucat (Deluxe Edition) — a suite of 49 monotypes as raw, as sophisticated, and as searingly personal as anything he has ever composed. Presented by DTR Modern Galleries, the exhibition is not merely an offering; it is an exhale after years of reflection, a love letter written in the silent spaces between rhythm and loss.

To understand Esper Lucat, one must first know the ghost in the room. At six years old, Furuholmen lost his father, a gifted jazz musician, to the indifferent violence of a plane crash. That absence, that hollow chord, threads its way through his music, his images, his very cadence as a creator. It is the reason why, even at the height of A-ha’s global ascendancy, Furuholmen’s gaze seemed perpetually fixed elsewhere — beyond the limelight, beyond the frenzy, towards something quieter and more sacred.

In this new body of work, he turns his attention to another master who understood the late beauty of abstraction: Henri Matisse. During the isolation of the pandemic, Furuholmen revisited Matisse’s final great work, “La Chapelle du Rosaire” in Vence. There, Matisse — old, ailing, and unburdened by earthly ambitions — had distilled his vision into pure color, pure form, pure faith.

Inspired by this spiritual audacity, Furuholmen created seven woodcuts, the Esper Lucat (Mourlot Edition). But where others might have stopped, satisfied by homage, Furuholmen pressed on, coaxing variation after variation out of the original plates, improvising as a jazzman might on a beloved standard. Seven structural and chromatic transformations later, 49 monotypes emerged, each a singular world unto itself — an exaltation of repetition, divergence, and revelation.

The palette is ecclesiastical: white for purity, purple for penance, red for martyrdom, green for hope renewed. These are not arbitrary choices, but codes—threads stitched through the fabric of memory and liturgy, vibrating just beneath the surface.

Visually, the works are bold, spare, almost calligraphic in their authority. Color blocks hum against emptiness. Letterforms dance, half-forgotten yet urgent. There is something feverish and prayerful in the compositions, as though Furuholmen is trying to pull meaning from the ether before it dissipates forever.

“I am interested in the place where meaning meets babel,” Furuholmen has said — and it is here, in the electrifying tension between word and image, between intention and chance, that his monotypes find their truest pulse.

The exhibition itself feels less like a static display and more like a liturgical procession. Each piece demands contemplation, each variation a whispered secret from a life spent in translation: between sound and sight, grief and grace, silence and song.

And of course, there is the irresistible glamour of Furuholmen himself — the Knight of the Order of St. Olav, the songwriter who gave the world Take On Me, the figure who can disarm a room with a glance and yet chooses, instead, to offer a hand-drawn prayer.

Esper Lucat — Hope and Light — could not be a more fitting title. It is what Matisse offered when he could no longer dance with a brush. It is what Furuholmen offers now, after a life lived across stages and studios, after a pandemic, after too many farewells.

It is rare to encounter an artist who has not only survived the machinery of fame but emerged from it burnished — vulnerable, luminous, still searching. In Esper Lucat (Deluxe Edition), Magne Furuholmen reminds us that art, at its best, is not a performance. It is a sacrament.

The exhibition will remain on view at the National Arts Club through May 30 with a reception on Friday, May 9. Attend if you can. Bring your better instincts. Leave your cynicism at the door.

Some works are meant to be seen. Others — like these — are meant to be felt.

For more information visit dtrmodern.com and follow @dtrmodern on instagram.