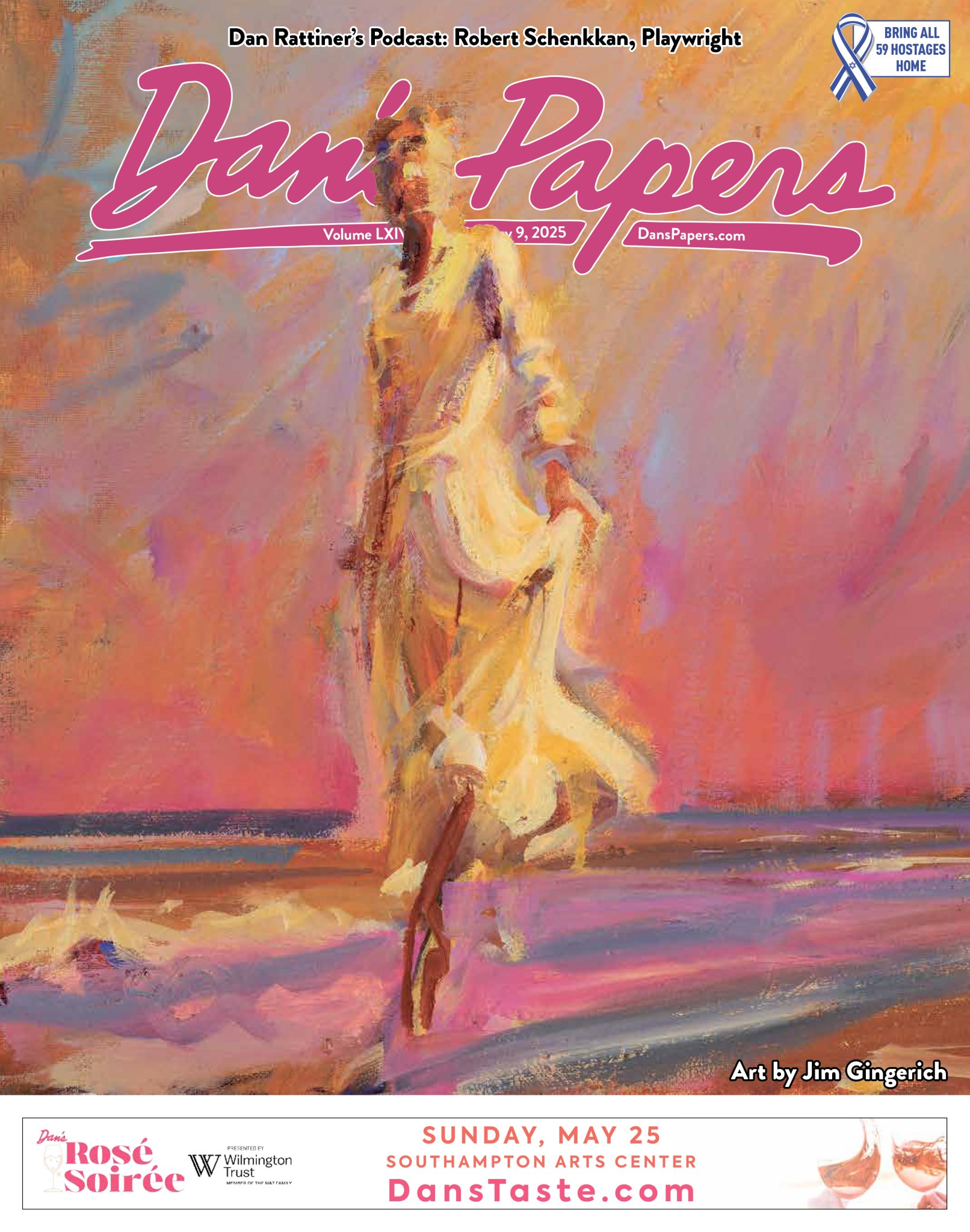

Jim Gingerich Honors Powerful Women in New Series

This week’s Dan’s cover artist Jim Gingerich offers a look at his early career and new work, including his cover painting.

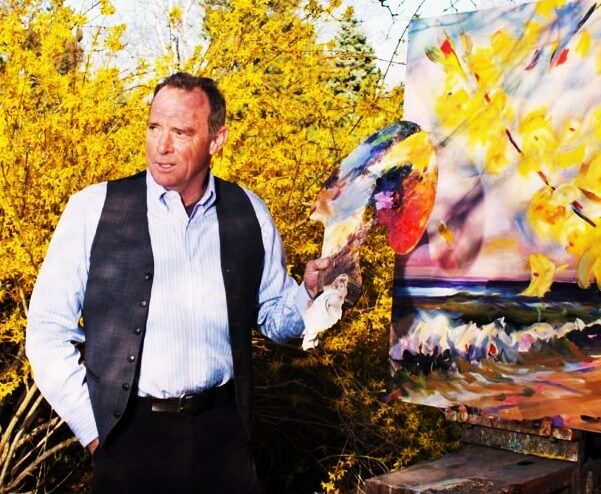

A Conversation with Jim Gingerich

Tell me about this painting. Your paintings can be quite varied across your total body of work. What is this series all about?

Powerful women.

My daughter, Danielle, is the inspiration for this series. She’s getting married in September, and as she searched for her wedding dress, she shared videos with me. When I saw her in the gown, I knew I wanted to work with that imagery.

The figures in these paintings walk along a Hamptons beach at twilight. Two are lit by the strong, warm sun; one is washed in moonlight. The figures both reflect light and seem to carry an inner glow. I wanted them to embody confidence and poise — a self-contained power and elegance.

The paintings feel like they’ve always existed — which is the goal — but each one went through many iterations, balancing space, light, and form, until everything sparkled and worked together.

Danielle exemplifies the best of the female dynamic — strong yet serene, thoughtful, wise. Her faith in herself, her joy, her strength wrapped in grace.

I’m dedicating this series to her.

How did you come to the Hamptons?

While living and working in Tribeca in the mid-‘70s, I’d drive my VW bus out to Montauk now and then, seeking the antithesis of bustling Manhattan — the silence between notes, so to speak. The solitude, sea air, soothing sound of the breakers, and open vistas — all were cleansing and grounding.

By the mid-‘80s, my good friend Terry Elkins (another Texas boy) had set up a studio in an old potato barn in Wainscott. We had many adventures on the beaches in Sagaponack — ice skating, surfcasting for blues and striped bass, swimming in the sea.

In 1988, my wife Diana Aceti and I rented a house on Parsonage Lane, and my love affair with Sagaponack was in full bloom. When it was time to return to our loft in Soho, I was reluctant to leave such a pure, inspirational landscape with so much charm.

By 1991, we’d sold the loft in Soho, and the Hamptons have been home ever since.

Can you talk about how the art scene has changed over the last 50 years?

In the mid-‘70s, you could buy an entire loft building in TriBeCa for $80,000. My rent for a small loft was $150 a month. I knew over 100 artists in the neighborhood — maybe two had trust funds. Everyone else worked to pay the rent.

It was possible then for young artists to follow a dream and build a career in Manhattan. Still daunting, but doable. And no gallery ever charged an artist to exhibit.

Nobody had a computer. No internet. 35mm slides, 4×5 transparencies, and word of mouth were your foot in the door. The art world was smaller, and deals were sealed with a handshake. I never signed a contract. I met or knew 98% of the collectors who bought my work — and they were engaged with the paintings, proud to hang them in their collections.

I remember visiting collector Harry Torczyner, who’d bought a piece from my first solo show in New York. In his penthouse, the first thing I saw was Magritte’s The Son of Man — the man wearing a bowler hat with the green apple over his face. I was impressed. Harry led me into another room where my painting hung between a Francis Bacon and a Claude Monet. Across the room, a large de Kooning. I was thrilled to be in the company of the masters.

Online sales are now necessary but compared to that experience they seem a bit impersonal and disconnected — but that’s another story.

You came to New York on May 1, 1976 and have found great success as an artist. What have you learned along the way?

I’ve learned that after 50 years of painting almost every day, I’m still as excited and enthusiastic as when I made my first painting in 1971.

I was a philosophy major at the University of Oregon (Eugene — the hippie capital of the world at the time). I studied Hinduism, Buddhism, Zen, Taoism, practiced kundalini yoga, contemplated chakras, and ate kale.

My father, a physicist, encouraged me to explore quantum energy fields, vibrational frequency, and light — the stuff of reality. It meshed with my passion for Eastern philosophy. He also loved the arts and took up painting as a hobby. He invited me to join him at a painting class at a local college and bought my first set of brushes and paint.

Our assignment was to turn our easels toward someone in the class and paint their portrait. Naturally I picked my father. As I made the first marks, mesmerized by how the canvas grabbed the paint, I had a Eureka moment.

Eric Clapton bought several large paintings from me a few years ago. Recently, I called to ask him about tickets for his upcoming Madison Square Garden concert. “How many notes do you think you’ve played?” I asked. He just laughed and said, “How many brush strokes have you made?”

After I switched my major to Fine Art — Painting, I studied with a Japanese teacher whose approach was filled with Zen wisdom, discipline and hard work. After earning my BFA, I packed my VW bus with art supplies, a drawing table, clothes and a guitar. Gas was 50 cents a gallon. I arrived in New York on May 1, 1976 and slept in my van until I found a small loft for $150 per month in what became TriBeCa.

When I made the first painting, I had no skill set whatsoever. Now I like to reach just beyond the skills I’ve honed in 50 years. Like treading water just where you can barely touch bottom. You’re out of your comfort zone but you know the bottom, the foundation is there if you need a springboard.

I’ve learned that space is as important as form — maybe more. And painting space well is very difficult. Space is not simply an empty void but rather a dynamic entity that interacts with matter and form influencing its behavior and shape. Like the silence between the notes in music, we don’t immediately notice but it’s silence that makes music possible. Space makes form possible.

As a young painter, I’d throw paint around like an abstract expressionist, forcing my will on the canvas. Over the years I realized: If I’m bringing this thing to life, it might have something to say during the process.

You make one mark, that’s a start, a singularity. You make two marks, that’s duality. You make three marks, that’s a story. These marks play off each other and energize the rectangle and at some point, the canvas becomes a dynamic system that has its own direction, its own agency, its own voice, its own consciousness. As I see this happen, I’m pulled into the dialogue and the dance begins. Off we go, never knowing how it all will turn out. There’s no choreography, no script, no rules. The painting is finished when the dialogue stops.

That’s one reason why I’m never lonely in the studio. Companions galore. Right now, I have 30 works in progress stacked around me. When I walk in, it’s the squeaky wheel that gets the oil — “Work on me!” Like a mother with a dozen kids, I often wonder: Who’s in charge here?

What else have you learned about oil painting and being an artist?

It was heartening recently to hear Paul McCartney say he really doesn’t know how to write songs. And Steven Spielberg admitted that before every movie, he’s never sure if he can pull it off.

It’s the same for me. Paintbrush in hand, standing before a canvas, fed, coffeed, dressed, ready for the day’s work, sometimes I feel totally in command but more often I feel like a prospector with a shovel in a vast desert. No one else is around. Okay, I’m here, I got my shovel. But why am I here? What am I looking for? And where do I start digging?

I have to crawl into the far tunnels of the psychic mineshaft, trusting the timber props will hold until I shine a headlamp in the darkest corner, the place I’ve never been before. Dig here. Let’s say I make the perfect painting, a world-changing tour de force, fulfilling on all levels, my masterpiece. What would I do the next day? There’s only one answer: I’d pick up a brush and start again.

Do you have any new projects or exhibitions underway or in the works?

Yes — an upcoming exhibition at The Church in Sag Harbor, honoring artists-in-residence over the past four years. Here and There: The First Churchenniel opens October 4 and runs through December 29.

Where can people see your work, online and in person?

Visitors are welcome to come by the studio, 15 W Harbor Drive, Sag Harbor, or jimgingerich.com, or call 631-871-1605

Cover art photographed by Gary Mamay