White Dress on the Diamond: A Story of Survival, Service & Softball in East Hampton

In recognition of Dan’s presenting sponsorship of the 2025 East Hampton Artists & Writers Charity Softball Game on Saturday, August 16, we are giving participating artists and writers free rein to write whatever they want in this space each month. Here, Elise Trucks of the Retreat, and daughter of Allman Brothers’ Butch Trucks, shares her Artists & Writers Game experience.

White Dress on the Diamond

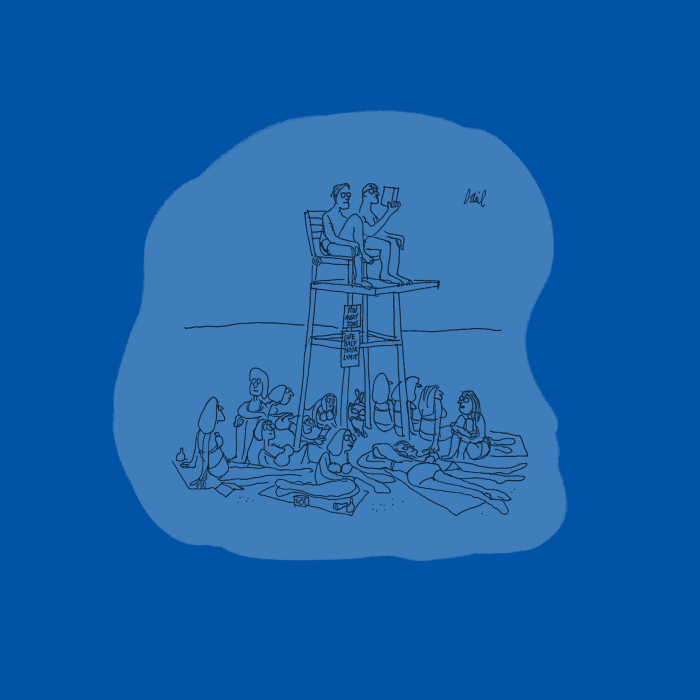

By any measure, it is one of the strangest annual rites of summer on the East End: artists with charcoal-dusted fingers squaring off against writers whose paper cuts haven’t quite healed, flailing at softballs under the hot, lazy skies of East Hampton. And over it all, the ghosts of legends — Bill de Kooning, Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer, George Plimpton — hover like mischievous umpires.

Since 1948, the Artists & Writers Charity Softball Game has been as much spectacle as sport. Beneath the trees of Herrick Park, it has endured—morphing from pick-up chaos to charitable juggernaut. Its dugouts once brimmed with the likes of Leif Hope, the unflappable impresario who shepherded the event into its modern form. The players have included Pulitzer winners and pranksters, heiresses and has-beens, all united by the absurdity of watching world-class talent swing and miss in spectacular fashion.

I am invited back each year. Not because I can hit — I can’t — or because I can field — I definitely can’t. My late father, Butch Trucks of the Allman Brothers Band, helped shape American music, blending jazz, blues, and psychedelia under Duane Allman’s visionary leadership. My cousin Derek, often called the greatest living guitarist, carries that legacy forward. I’m a drummer—still learning, still loud—but honored to play in the same family band, at least in spirit. I suspect my invitation to play in the famed softball game each year is out of respect for that legacy. And since there’s no musicians’ team, I join the writers.

Two summers ago, I found myself improbably at bat in the first inning. Ken Auletta had sworn I wouldn’t have to play; but there I was, face to face with President Bill Clinton, who had strolled out to call the plays from behind the pitcher’s mound. I struck out, of course. But in the 9th, the writers mounted an unlikely rally. Bases loaded, three runs behind, Rabbi Franklin knocked it out of the park, and we won. Absurd, unforgettable, and perfect.

This year, for me — and for many — the game feels different.

At The Retreat, where I now lead marketing and development, we know that survival looks nothing like the playful skirmish of an August ballgame. Survival is what Amanda found.

In the Toyshop Media video that plays before our June 7 benefit, she wears a white dress, sunlight pooling around her shoulders, her voice steady despite the weight of memory. Amanda came to us with her children, fleeing unspeakable domestic violence. At The Retreat, she found shelter — and a team who would fight for her. She speaks softly of the terror, of running for her life, of a fear so constant it became her atmosphere. The bruises faded. The nightmares took longer. The safety, the shelter, and the hope? That came from The Retreat.

Since 1987, The Retreat has stood in the quiet shadows of wealth and privilege to do the unspeakably hard work: providing emergency shelter, legal advocacy, trauma-informed counseling, and a 24-hour bilingual hotline for survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and human trafficking.

This year, we face our own terrifying uncertainty. In reevaluating its commitment to human services, the federal government has frozen and rescinded many contracts. Our funding gap could swell to more than half our annual operating budget. Survival, for us, suddenly mirrors that of the clients we serve. We are fighting to stay on our feet while the need around us grows. We are fighting to keep the doors open for the next Amanda.

And that is how the Artists & Writers Game, improbably, becomes more than a game.

Leif Hope understood this from the beginning. He was the one who institutionalized the game’s charitable mission in the 1970s, creating the now-famous red-and-blue caps and bringing in sponsors to support the work of local nonprofits. Over the years, the game has raised real money for organizations like the Eleanor Whitmore Early Childhood Center, East End Hospice, Phoenix House, and The Retreat. The list of past players reads like a rollicking East End who’s who: Alec Baldwin’s sardonic wit at shortstop, Christie Brinkley’s sunlit swing in the outfield, Mort Zuckerman smirking from the sidelines, and Carl Bernstein—history’s byline in cleats — coaching near the dugout with quiet intensity.

The tradition remains gloriously weird. Last year, as a seagull strafed left field, I stood warming up beside a poet who confessed he had never before worn a glove. On the mound, an artist delivered pitches so surreal they seemed a tribute to Salvador Dalí. Nobody cares who wins. But everyone cares that we show up.

As I stood behind home plate that summer afternoon, the sun slanting through the sycamores, I imagined Amanda in her white dress. She stands for the hundreds of women, men, and children who will never take the field or sit in the stands, who will never cheer or complain about a bad call. They are rebuilding lives in silence and dignity — because The Retreat caught them before they fell.

So I swing, miss, swing again—and run anyway. Because every dollar we raise on this absurd, beloved diamond can mean the difference between danger and safety, between silence and a voice, between despair and possibility.

There will be laughter. There will be bad throws. There will be applause when a screenwriter — “Shakespeare”—snags an impossible pop fly. There might even be another 9th-inning, bases-loaded, Rabbi Franklin moment. But when the field is raked and the bats are stowed, there will remain a cause worth fighting for.

We are still swinging.