Why You Do or Don't Cheat: Promiscuity Explained

Surveys show that 90% of Americans feel it is immoral to cheat on their mate. They also show that about 20% of married men cheat anyway and about 12% of married women do, too.

This tells us that some, but not all, people who cheat think cheating is immoral. This tells us that married men must sometimes cheat with a woman who cheats with more than one man, and this tells us that men try to make their women stay-at-homes so they can know the children are really theirs. It also tells us that some people, in the cheating department, feel they cannot help it. That’s a lot. But until now, that’s all there’s been. This year, however, scientists say they think they know WHY people cheat.

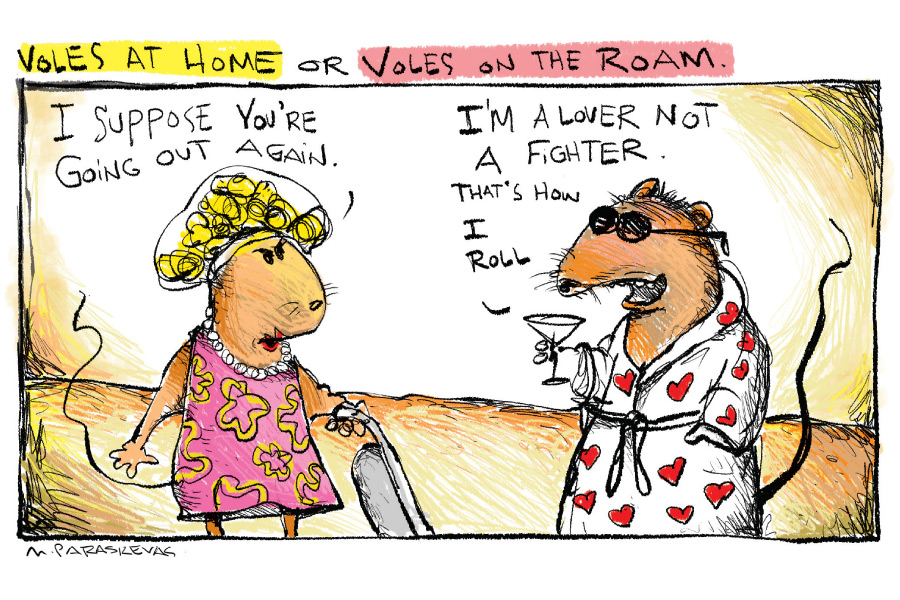

About 10 years ago, a famous study was done involving a little furry animal called a vole. There are two kinds. Prairie voles live in burrows on the plains. Montane voles live in burrows in the woods. Biologically they are otherwise very alike. However, male prairie voles stay true to their mates for life and are part of extended families. Male montane voles, though, are wildly promiscuous. A female comes along and off he goes. There’s no family life.

Intrigued by this situation, Dr. Thomas Insel, who is now the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, discovered that a hormone called vasopressin was at a very high level in the voles who were faithful but at a much lower level in the voles who fooled around. Thinking this through, Dr. Insel removed some of the hormone from the male prairie voles. The male prairie voles came out of the burrows, looking for women. It also worked the other way around. With more vasopressin, the males in the woods stopped fooling around and instead fell in love and snuggled up with a favorite female and stayed with her. This surely screwed things up in those vole communities. What the hell was that guy doing?

Dr. Insel was also able to manipulate the females in a similar way, but by using a hormone called oxytocin. He changed librarians to pole dancers. He changed wild women to suburban housewives. That’s all figuratively speaking, of course.

In the course of things, Dr. Insel also discovered where in the vole brain this hormone was received. He found that where it was received affected the behavior of the voles. Receptors in the brain for those who were faithful were located in a place where warm and fuzzy feelings entered. But the receptors for those who chased skirts were where fearful and anxious feelings entered.

Now scientists say they have found a similar situation among humans. The study was done by psychologist Brendan Zietsch, of Queensland, Australia. He traced the record of more than 7,000 Finnish twins, now grown up. He contacted them and asked them all if they were today in a relationship for more than a year. For those who were, he asked if they’d had sex with a second person during that year. Guess what. The vasopressin and oxytocin levels and locations were exactly the same as with the voles.

Yes, it will be possible to mess with the receptor genes and change things. Parents who live upright moral lives could, at conception, arrange things so their babies grow up to adhere to the philosophies of the adults that make them. There will be no more black sheep in an upstanding family that tomcat around. There will be nobody in a swinger commune who just wants to keep his nose in a book. And what will become of the secret romance, the chase, the scorned lover, the philanderer and the Order of Protection? Ah, well. There goes literature and the arts.

But wait. During the last six months, three couples I know who met on online got married. Did they exchange vasopressin receptor information?

I’ll ask.

A lengthy story about this appeared in The New York Times on June 3, titled INFIDELITY LURKS IN YOUR GENES.