Elephants of Burma: Damned if You Do & Damned if You Don’t Isn’t Just About Our Deer Problem

The Hamptons has a deer problem. Some people want to hunt them to reduce the herd. Others want to put feeding posts out so they don’t starve during the winter. Others want to dart them to sleep and cart them off to the Adirondacks. Nobody really knows what to do.

Recently, I have been reading about the elephant problem in Burma (now called Myanmar). And it makes me give thanks that all we have is a deer problem. And it’s not just that an elephant is 30 times the size of a deer or that when angry an elephant can kill people—300 people in Myanmar get killed by marauding elephants every year.

And it’s not just that elephants are smarter than deer—they never forget, as you know. It’s all of the above and more.

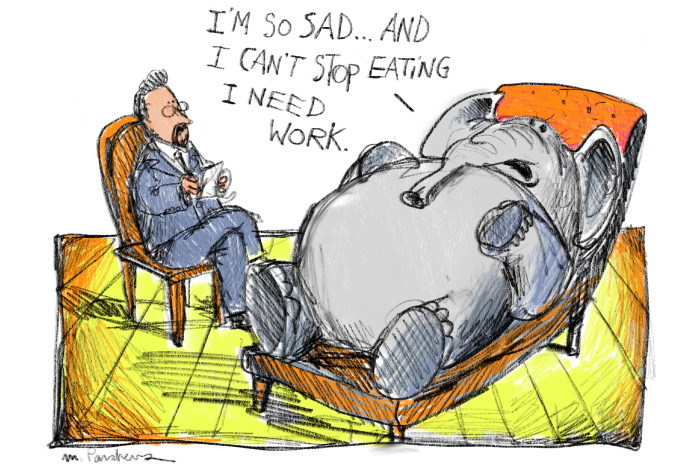

For example, elephants have feelings, and as things are developing, they are getting very upset. It’s about the work.

In 1824, the British came to Burma and discovered teak. Teak is extremely heavy. Just the trunk of one tree can weigh as much as two tons. With their primitive steam engines in those early days, the British had all sorts of trouble hauling felled teak trees down to the river, where they could be floated off to a sawmill. They’d have to destroy much of the surrounding jungle to get the trees down.

Soon the British found that elephants, chained to teak logs, could carefully drag the trees down established paths at little expense without destroying the surroundings. By 2008, there were 5,000 timber elephants in Myanmar, using chains, hauling teak out of the forests.

But that came at a cost to the elephants, according to a study done and published in Time magazine that year. Elephants in the logging industry—2,851 owned by the government and around 2,700 owned by private companies—were suffering from heart disease, eye problems or other health infirmities. Yes, there were camps where retired elephants could go, but they didn’t have enough resources or doctors to handle the problem.

Kind of reminds me of the concussion problems we see in the NFL and college football.

As a result of this, on April 1, 2014, a new law went into effect in Myanmar banning logging for export. It was supposed to help save the elephant herds from this hard work, and it was also supposed to make more teak available for domestic use. But local teak is not in demand. Instead, the law has caused the near collapse of the billion-dollar teak export industry in Myanmar.

And now it has created an unforeseen problem. It’s almost two years since the law passed. And last week, The New York Times published an article about it.

“UNEMPLOYED, MYANMAR’S ELEPHANTS GROW ANTSY AND HEAVIER” was the headline.

Who knew?

I have often commented on The New York Times’ ability to not rest until they can make readers feel bad and helpless about something they can do nothing about for the rest of the day. (A photo on the front page of the Times today as I am writing this shows a man standing by a wall. The caption reads “Jose Francisco Molina Sierra said that food was scarce in Puerto Cabello, Venezuela, but that medical care was in worse shape.” But that’s another story.)

Well, back to the elephants of Myanmar.

According to Times last week, the elephants in Myanmar, now out of work, are suffering emotional problems. They had loved working, hauling teak around. But now that is over.

“They become angry a lot more easily,” U Chit Sein, age 64, told the Times. “There is no work, so they are getting fat. And all the males want to do is have sex all the time.”

The Times article makes the case for elephantine post-traumatic stress disorder. The elephants had a purpose, a mission. Get those trees down to the river. The elephants were well treated by their uzi (elephant handlers), they were given treats, complimented for a job well done, allowed to work free and outdoors, forage when they wanted, keep to an eight-hour work day five days a week, with retirement at 55, mandatory maternity leave, summer vacations and good medical care.

By the way, I am not making this up. That last sentence is a direct quote from the article in the Times.

An uzi kept a log of the workday of each of the elephants. So the elephants, by looking in their log book, could develop pride in their work. A veterinarian with Elephant Care International, Dr. Susan Mikota, told the Times that the working elephants have good muscular and skeletal body condition and get good exercise. And they are on a natural diet.

Studies have been made comparing elephants in zoos with elephants in logging camps. The zoo elephants die younger, give birth to obese baby elephants and are more lethargic. We can’t just put all these unemployed elephants in zoos or circuses. And we can’t put them back to logging by getting rid of the law. Nearly half the forests of teak in Myanmar have been cut down.

So now they are discussing letting these elephants out into the wild.

In the Time article from 2014, the idea of letting these unemployed elephants back into the wild was causing considerable concern to the Myanmar people. Angry 10-ton elephants all over the place. It would be a catastrophe. People would be attacked, gored and killed even more frequently than they already were.

But in the Times article last week, environmentalists applauded the idea of releasing the elephants back into the wild. This is where they belong, out free, back to nature. On the other hand, doctors expressed fear that these released captive elephants could spread new diseases to remaining wild populations of elephants. Agricultural experts meanwhile said the great herds of new elephants in the wild could mean the crippling of farming. How do you keep them away from the crops?

The government already has a law that reimburses the farmers for lost crops to the wild elephants currently out there.

So what’s to be done?

Love has to be taken into consideration.

“I don’t know what I will do with my elephants,” Mr. Saw Tha Pyae told the Times. “I will never sell them, never! I love them so much!”

I have my own ideas about this. The elephants should be shown what we do when there is no more physical work to be had.

Have them haul the same teak log from deep in the forest down the trail to the river, and then back up to the forest 50 times a day. Give them those wrist bracelet exercise trackers. They can keep score of how many times they do this. They can monitor their heart rates and their steps. They can take naps and count the hours doing that. They can see how well they sleep—how much is light sleep, how much is heavy sleep—and how many hours and minutes they sleep.

My plan is we create these giant rubberized tracker bracelets—waterproof, but take them off when you go swimming—and just wrap them around the elephant’s trunk down toward the end.

They even tell you the time. Just pick up your trunk, bring it up to your eyeball and check it out.

And the uzis, with clipboards and whistles, can coach them.

A happy elephant is a healthy elephant. We all know that.