Book Review: Genevieve Sly Crane's 'Sorority' Is a Novel for Everyone

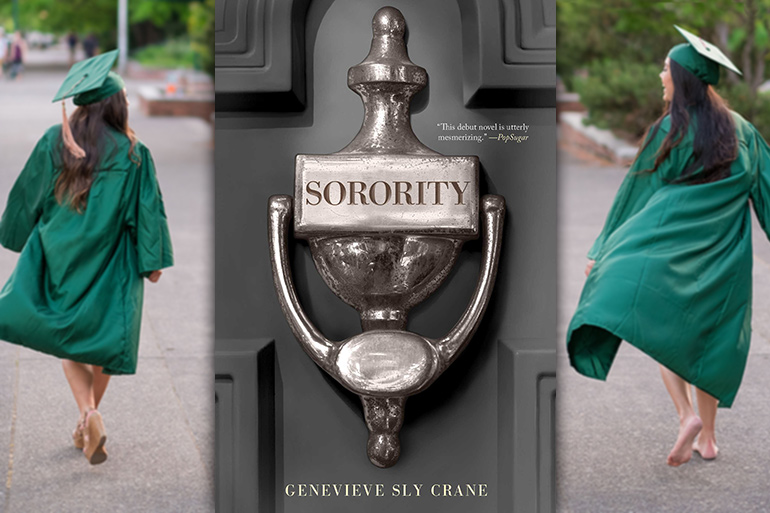

If you’re browsing the shelves at your local bookstore this summer, you’re guaranteed to come across Genevieve Sly Crane’s debut novel, Sorority (Scout Press, $26). After all, when people talk, bookstores listen—and people are talking about this novel.

First, some housekeeping, so to speak. Sorority, despite being primarily populated with female characters, is not “chic-lit.” Also, despite its title, Sorority is not replete with Hollywood tropes of binge drinking and sex-fueled college frat parties (quite the opposite). One needn’t have been in a sorority in order to “get” the novel.

Sorority, in fact, isn’t about a sorority, so much as an examination of the lives of a sorority’s sisters. A man browsing the stacks shouldn’t pass it over simply due to its title and the femininity it suggests. Any non-grandmother who has read The Summer Book by Tove Jansson—a book that has some similarities with Sorority—should know not to judge a book by its characters.

If you’re looking to begin a book club, Sorority is fodder for robust conversations between book-clubbers of all ages. The relatively short and engrossing chapters make Sorority the perfect beach read. The careful, tragic language makes Sorority a before-bed read that, well, might actually keep you up all night.

The themes and ideas presented in Sorority bring to mind a reader curled up in front of a fireplace on a rainy day, pausing at any one of countless sentences that require a moment of contemplation. All of which is to say, there’s nowhere and no place where Sorority can’t or shouldn’t be read.

Crane, a 2013 graduate of Stony Brook Southampton’s MFA in Creative Writing and Literature program, was the Pledge Mistress of her own sorority as an undergraduate, so we’re pretty sure from the start that we’re dealing with a capable author who knows her subject.

Once Sorority begins, any doubt is dispelled. Straight away, we are introduced to the ensemble cast as a chorus in the novel’s opening chapter. In Classical Greek drama the chorus was a group of actors who described and commented upon the main action of a play with song, dance and recitation.

The main action reverberating through this Greek-life drama is the death—or was it suicide?—of Margot, former occupant of Room Epsilon, where no one lives now.

Readers are first introduced to Lucy and Shannon, two Massachusetts girls, childhood friends who, unbeknownst to each other, are pledging the same sorority. We follow the two girls through ages 11, 12 and 13; into their sophomore year of high school when their friendship abruptly ends.

We meet Twyla in a psych ward, there on suicide watch—and Twyla’s dead father who haunts her, invisible to everyone else, from the corner of every room. Deidre, a naked sushi model and Margot’s girlfriend. Kyra, who was evicted from the sorority for having become pregnant. Stella, who thought she was spending a romantic weekend in the woods with her frat-brother boyfriend, but ended up being left alone in a cabin in the middle of nowhere.

Throughout the novel, Crane threads the lives of these sisters and others into an elaborate web of vignettes, each providing insight into the lives of the sorority’s sisters and their relationships both with each other and with the outside world. We find sisters with eating disorders and unplanned pregnancies, victims of drug abuse and sexual assault—real life tragedies set in a Greek one.

In Sorority, Crane constructs approximately two-dozen realities, each as carefully similar as they are unique—each story playing with and against the others in interesting and compelling ways, moving along with even more interesting and compelling language. Small details are dropped here and there, sisters are referenced in passing, connecting the stories and, in a way, answering a philosophical question: How does one know, outside of their own experience, that anyone else exists.

Sentence for sentence, Sorority might be the best new book you read this summer.