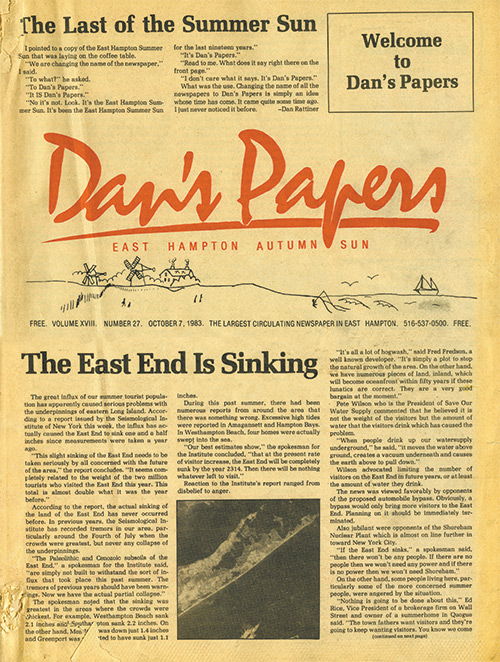

How It All Began: Dan’s Papers’ First Office Was a Bedroom at the Publisher’s Parents’ House

On the morning of Friday, July 1, 1960, I went out to my 10-year-old Chevrolet sedan to where 5,000 copies of the first Dan’s Papers (then called The Montauk Pioneer) were tied up in bundles in the front seat, backseat and trunk, drove off and began delivering 20 or 30 or 40 copies to each store, motel and restaurant in Montauk. I’d set them on counters, on cigarette machines, on tables and shelves.

There were 140 businesses in town. I’d counted them. Going along streets, delivering bunches of papers one handful at a time, it took me the next 10 hours. I had not asked anyone ahead of time if I could do that. It was a surprise. Store owners would examine what was put out. So everybody could read a copy and decide if they wanted to keep it for the customers or not. The papers were free.

And I the college student—I was 20 years old— was convinced people would like my newspaper. I took that risk. And at the end of that first day, hot and sweaty with all the papers gone and just bits of newsprint and cut-up twine to show for it on the floor of the car, I drove down to the beach in the center of town, parked, took off all my clothes down to my shorts, and ran over the dunes, across the sand into the ocean to splash around as the sun set. It was wonderful.

Since that day, and for the rest of my life, nearly 60 years later, I have published this newspaper.

John F. Kennedy was running for president that first year. New cars were sporting tailfins (not my old car). Montauk was a brand new summer resort town filled with visitors on vacation, and it did not have a newspaper to call its own. I thought I could publish one. Be a booster for the town. Tell its storied history. And tell people where to go and what to do. And I thought if I gave it away for free, it would succeed on advertising revenue alone, and I was right.

It took a lot of planning the prior winter to develop the idea. I had been thinking about it while off at college upstate. We had a college newspaper that got distributed free on campus. It was placed in stacks in wooden bins in 10 locations. Everybody read it. But no one had ever thought to distribute a commercial weekly town newspaper for free. Not on Long Island, not anywhere.

I put a sign on my bedroom door in my parents’ house on South Fairview Avenue. This would be my office. I began typing stories, making lists of prospects and locations to distribute, calling to get printer estimates.

I was not from Montauk. My dad had brought me and my sister and my mom out to Montauk from Millburn, New Jersey, three years earlier when he bought the drug store in Montauk. He was a pharmacist, but he was also a fisherman. We came along. I had just finished up at Millburn High.

After my second summer home from college, working for my dad as a clerk and stock boy, my mom said if I wanted to I could go to pharmacy school and take over from my dad some day.

This was the last thing I wanted to do. I wanted to be outdoors, meeting people, writing stories, selling advertising, going into the publishing business, entertaining the tourists. I’d worked for the college paper. I’d worked for the high school newspaper. I had ink in my veins, is how journalists described themselves then.

The way I saw it was that if I could sell 30 merchants 1/12-page ads for the summer ahead of time, I could pay the printing bill, gas for my car and other expenses and make twice the amount of money I was making working for my dad. Dad liked the idea. He said he’d be proud of me if I could do that.

The year before the launch—Eisenhower was President—about to go off to college for my junior year, I walked around with a pasted-up dummy of what the paper would look like and pitched my newspaper to all the merchants just closing up their businesses for the long winter. Many said nobody would read a newspaper if they didn’t pay for it. I said people would read my newspaper. It would be interesting, funny and about the town. And I could give out 25,000 copies free, all summer. There were only two places in town where you could buy a newspaper, and one of them was my dad’s store. Might be able to sell 100 copies in a good week.

In that first issue, to prove my point, I published a fake ad. It was for a mail order product—the MacKenzie Seagull Whistle. Take your jeep out onto the beach to go surfcasting, and, if you get stuck in the sand, take out the whistle and blow it. Seagulls would appear and push you out of the sand. Watch for this whistle soon for sale in a store near you.

Everybody was talking about this in town after that first issue came out. Everybody. I had proved my point.

At the end of that summer, my dad took me to Plitt Ford in East Hampton and bought me a three-year-old silver Ford Fairlane Convertible 500 with red leather seats, whitewall tires and tailfins. Also at the end of that summer, as it turned out, I had made enough money to pay my tuition and college expenses for the next year.

In my fifth year, I was now in grad school, I sold so many ads in the springtime for the Montauk paper and now for a new edition of the paper in East Hampton that I needed to borrow $1,000 to get me through to a time when all the money would come pouring in later in the summer.

I dressed in tie and jacket and went to see Merton Tyndall, the 65-year-old President of the Bridgehampton National Bank. I laid on his desk all the contracts I had sold for the upcoming summer. I told him I didn’t understand how if I was more prosperous why I would have to borrow, but I did. I needed $1,000. He said that’s what banks are for, and he opened a desk drawer, took out a checkbook and wrote me a check for $1,000 and handed it to me.

“Do you want me to sign anything?” I asked.

“Nope. I see you are going to pay it back.”

I left.

The following year we did it again for $2,000, and the year after that it was $5,000.

A week after he gave me the $5,000 he called me up and asked me to come in.

“I hate to bother you,” he said. “But some people from the government are here and say I have to have you sign for this loan. I told them you always pay it back, but they said I should have you come in anyway.”

So I did that.

It’s been a long, wonderful ride from those years to this. I’ve loved every minute of it.

A beautiful book coming out this holiday season—60 Summers: Celebrating Six Iconic Decades on the East End—will consist of 60 full color glossy paintings together with commentary about them that I’ve chosen to grace the covers of the newspaper during these years. They are among my favorites and I hope you enjoy them.

I would love for all our readers and friends to be part of this wonderful book and support this historic project. To find out how you can get a copy and get your name in “60 Summers,” visit FriendsOfDans.com today!