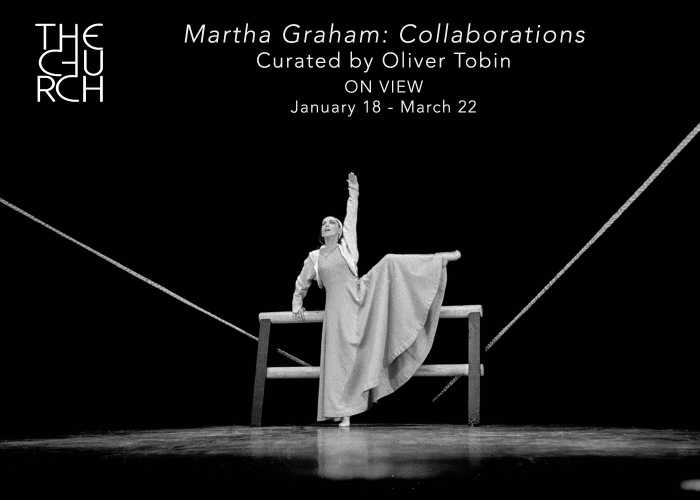

Review - Bob & Jean: A Love Story at Bay Street Theater Overflows with Romance & Nostalgia

Bay Street Theater officially kicked off its summer season on May 31 in Sag Harbor with Bob & Jean: A Love Story, playwright Robert Schenkkan’s unabashedly romantic homage to his parents.

As its title makes clear, this is every inch a love story. But don’t be misled. Yes, it’s light and airy, but it’s in no way insubstantial; it’s optimistic but not naive; elegiac but not maudlin, old-school but not old-fashioned.

And from its narrative structure to its production design, Bob & Jean is also extremely inventive. That shouldn’t come as a surprise given that Schenkkan has earned some of the most prestigious hardware in American theater over a long and prolific career.

All the Way, Schenkkan’s story of Lyndon Johnson’s efforts to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act, was awarded the Tony for Best Play in 2014. And the playwright’s The Kentucky Cycle, a nine-part deep dive into two centuries of American history, won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1992.

With Bob & Jean, Schenkkan once again turns to America’s past to tell his tale. Using World War II as a backdrop, he mines his own family’s history to create a literal love letter to his mother and father.

Schenkkan has been living full-time in Sag Harbor with his wife, Deborah for the better part of a decade. Writing in Dan’s Papers last month as Bay Street was preparing the production for opening night, he noted that the idea for the play began to percolate during the initial stages of the pandemic in 2020.

Since he was a child, he had always been aware of a dusty stack of letters his parents had written to each other during the war. But he had never really explored the stories they might tell, the secrets they might hold.

“Of course, we think we know our parents, but only through the brittle lens of our own needs,” he writes. “During COVID, Deborah and I hunkered down in Sag. It was a time for reflection, for taking stock, for considering the question Jean had often asked, “‘What makes a life worthwhile?’”

Schenkkan believed that at least a partial answer to that question might be found in his parents’ letters. And there they were, “neatly tied up with ribbon.” With the world on lockdown, it was finally time to read them.

The letters became Schenkkan’s source material and his lodestar. He set about reimagining his then-achingly young parents for the stage: an aspiring actress from Palm Beach destined for a traveling USO production of Arsenic and Old Lace and a Brooklyn kid destined for bomb disposal duty in the U.S. Navy meet in early-1940s New York City, first as friends, then later, as lovers.

On its face, Bob & Jean is a simple story, very much rooted in the real lives of real human beings. But in the hands of director Matt August, scenic designer Stephen Gifford, a solid three-person cast and the rest of the creative team at Bay Street, Schenkkan’s fabulously imaginative script takes flight.

Since the play’s entire mise-en-scene is structured around an exchange of letters, the set literally becomes an embodiment of written communication in an era that predated texting and email by many decades. Oversized postcards and letters on the theater’s wall and floor don’t simply adorn the set, they literally become the set.

Schenkkan’s script draws on actual snippets and ideas from the letters his parents exchanged. And since most of the onstage action takes place when the two main characters are thousands of miles away from each other, he needed someone or something to bridge the divide. His solution was to write himself into the play.

“Here was their son, now in his 60s, a father on his own, looking back at his parents in their 20s,” Schenkkan writes about his process. “I was not only discovering things about them, but I was also having my own revelatory journey. Now, instead of a duet, we had a trio! I could question them directly and they – gulp – could question me as well.”

In a moving and multi-layered performance, Scott Wentworth steps into the role as Schenkkan’s doppelganger, aka, “The Narrator.”

Wentworth is tasked with anchoring a play that takes place wholly within his character’s mind. And he more than rises to meet the challenge. He’s partly a traditional narrator but also partly something else entirely. He paces and prowls around the stage with the restlessness of a man with a life’s worth of questions. He muses about his parents’ motivations and intentions and every aspect of their inner lives. He wonders aloud about the half-clues, partial truths and multiple meanings inherent not only in Bob and Jean’s letters to each other, but also in their actions during the many months they spend apart.

Wentworth’s performance as The Narrator is sublime – searching and human and genuine. But he does not overshadow Jake Bentley Young and Mary Mattison, both of whom shine as Bob and Jean, respectively.

The two young actors hit many of the right notes, embodying the zeitgeist of World War II-era America tinged with a patina of nostalgia. This is the Greatest Generation writ large.

Mattison’s Jean is spot-on as the plucky, can-do female archetype with whom you might have expected to share a cup of coffee in 1943. But she’s much more than an ingenue. In fact, the script makes sure to stress her character’s bona fides as a serious stage actress. When she wavers about her relationship with Bob – or about giving up her career to live a more traditional life as a wife and mother – she keeps the audience firmly rooted in the realities of so many women born into that particular moment in American history.

Young has many fine moments as Bob as well, especially when he suspects from the tone of one of Jean’s letters that she might be moving away from him emotionally. But the most compelling aspect of his performance comes when Bob is at his most reflective and vulnerable, delivering a brief but powerful soliloquy describing his thoughts as the United States dropped the first Atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Of course, every love story worth its salt needs to show the audience a chemical reaction. And Mattison and Young certainly deliver one.

In narrative terms, Bob and Jean are figuratively apart far more often than they are together. Sometimes they read each other’s letters from opposite ends of the stage with The Narrator always close by to deconstruct the action. During those scenes, the physical and emotional longing the actors create is palpable. And when the couple actually makes physical contact, Mattison and Young melt into each other with a reckless and wholly authentic intensity.

It’s been said that nostalgia is an irrational desire to live in a past that never was. Though it occasionally meanders to the brink of hagiography, Robert Schenkkan’s knowing script never falls into the overly sentimental abyss. Such is the playwright’s craft. In the end, Bob & Jean: A Love Story delivers a stirringly romantic and nostalgic glimpse into two quintessentially American lives.