Ecology of Quilts: Natural History of American Textiles at the American Folk Art Museum

On view at the American Folk Art Museum, An Ecology of Quilts: The Natural History of American Textiles maps the environmental, material, and labor dimensions of quiltmaking practices spanning the 18th–20th centuries. Presenting 30 quilts from the museum’s collection of over 600, the exhibition sheds light on the intricate web of textile production, entangled in the colonial domination of peoples, flora, fauna, and fungi.

Quilts have sporadically been the subject of major museum surveys since the 1971 exhibition Abstract Design in American Quilts at the Whitney Museum of American Art, followed three decades later by The Quilts of Gee’s Bend—also at the Whitney—a deep dive into the rich creative practices of a small, historically Black, rural Alabama community of makers. A resurgence in art world interest over the past several years has brought quilts and their makers back into the spotlight. “Ecology of Quilts” curators Emelie Gevalt, the American Folk Art Museum’s Deputy Director and Chief Curatorial and Program Officer, and Austin Losada, Art Bridges Fellow, take a fresh approach to the rich history of quilts, grounding their inquiry in the origins of the materials themselves and the impacts—both generative and destructive—of their extraction.

Traversing the first, corridor-like gallery, visitors are immediately drenched in rich colors and greeted with an array of didactic displays. Warmth radiates from a glorious swath of blood-orange, intricately stitched wool centered on the right wall; the object label speculates that the color derives from either madder root or the cochineal insect (Spanish colonizers developed cochineal dye for their own uses based on exploited Indigenous knowledge). Opposite the quilt is an assortment of small jars containing both madder and cochineal, as well as indigo cake, woad powder, and dried weld. From just these five plant- and insect-derived materials, an entire color spectrum can be achieved. Although mesmerizing, the juxtaposition of luxurious textiles with the dried bodies of insects prompts viewers to consider: what is sacrificed for the sake of whose aesthetic enjoyment?

Beyond the knotty history of dye production, the exhibition delves into the colonial legacy of the textiles themselves. Cotton, unsurprisingly, takes center stage as the eventual crux of an American economy built on enslaved labor. Wool, linen, and flax were common in both domestically produced and imported textiles. Silk—due to the highly specialized cultivation of silkworms necessary for its creation—remained a luxury fabric and therefore features sparsely in early American quilts.

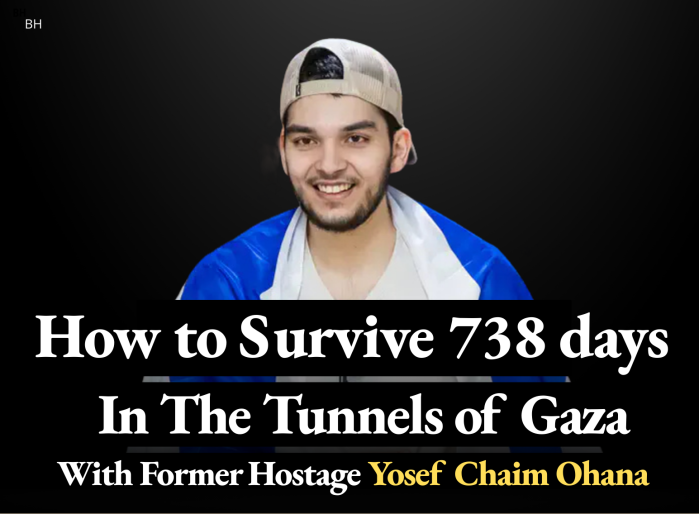

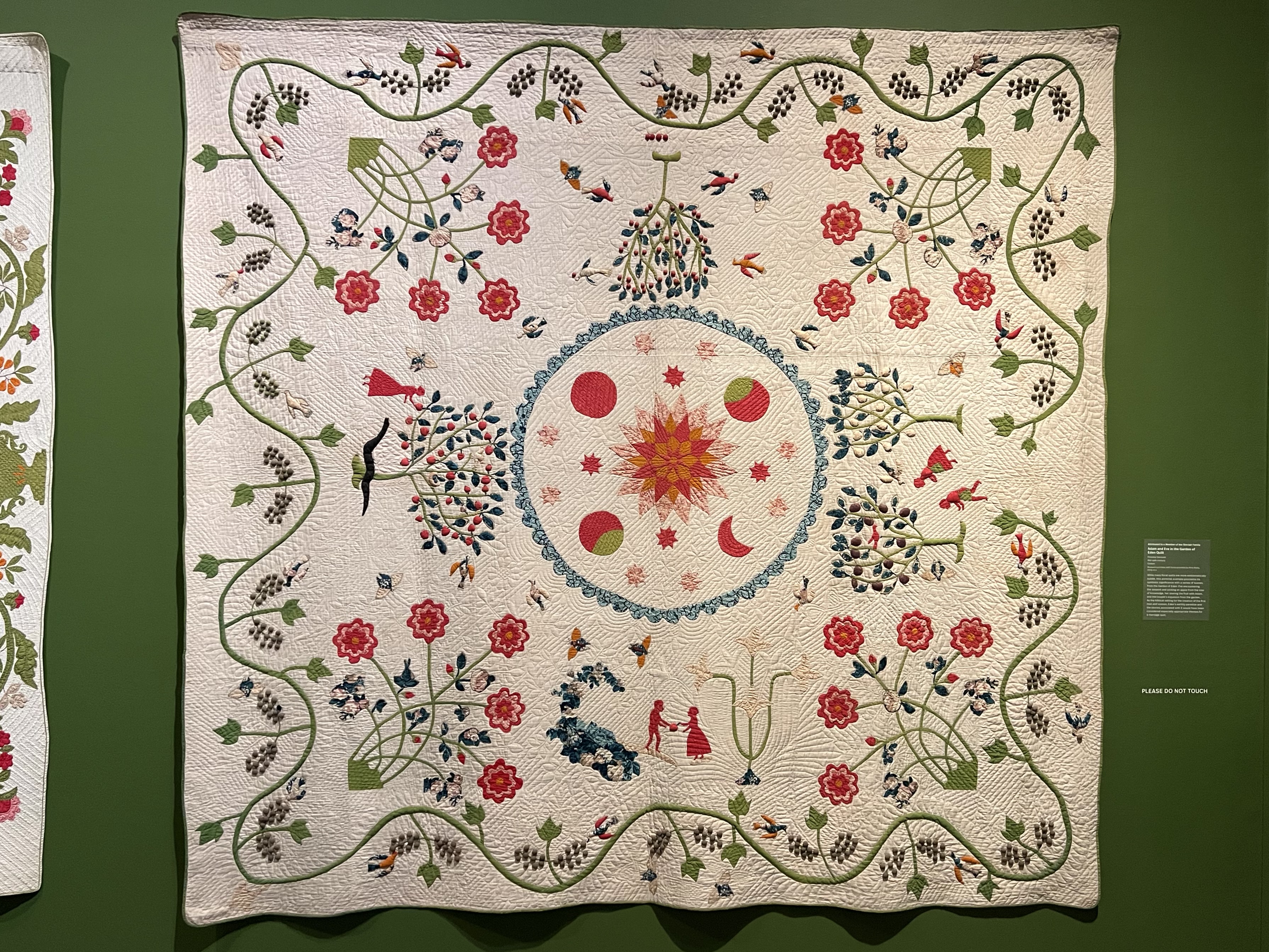

The central gallery highlights the symbolism of botanical motifs in quilts and the modicum of freedom that botany granted women in the 19th century compared to other fields of scientific study. A square, mid-19th-century marriage quilt depicts Adam and Eve amid a sea of familiar symbols: flowers, grapevines, a serpent, an apple, and two (clothed, notably) figures representing Adam

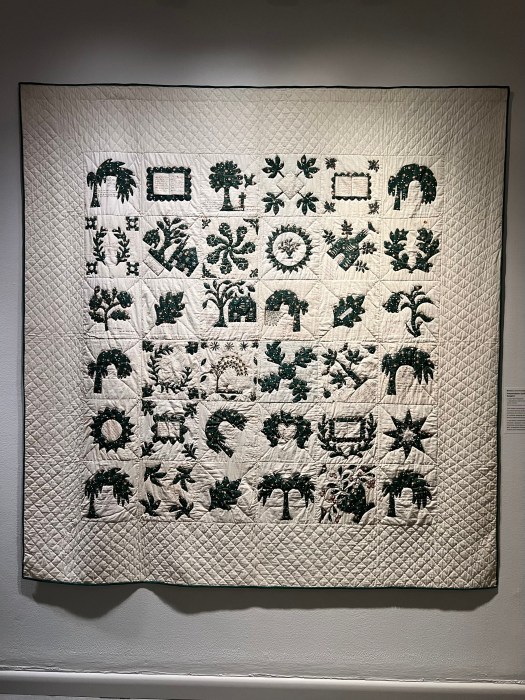

and Eve. Presentation Quilt for William A. Sargent, an album quilt created in Loudon, New Hampshire, around 1854, is rich with weeping willows, a symbol of mourning associated with the Rural Cemetery Movement.

Women quiltmakers during this period engaged in botanical study beyond decorative motifs, however. While women were largely shut out of the sciences, botany was considered a feminine pursuit. Many women, therefore, pursued this line of inquiry through school instruction, gardening, and personal observation, weaving their expertise into their textile work.

Bringing quilts—which historically have been shut out of the realm of art, due to their associations with femininity and domesticity—into an artistic setting is always fraught. The question arises: how should quilts be displayed to do justice to their context while still honoring their artistic merit?

The curatorial decisions that went into “An Ecology of Quilts” toe the line between institutional grandeur and domestic intimacy. The warmth that suffuses the space, partly due to the green walls, evokes a cozy living room while also grounding the textiles in the plant world.

In a section highlighting the popularity and origins of “chintz”—a Hindi-derived term loosely defined as embellished cotton, often connoting a lustrous finish achieved through various combinations of wax, starch, and heat—quilts unfurl from wall-mounted dowels, emphasizing their tactility and usability.

Beyond traditional text-based wall labels, prints and illustrations depicting various stages of the process— such as immersing fabric in an indigo dye bath—interspersed the quilts that line the walls. A watercolor illustration placed next to the red-orange quilt in the first gallery, for instance, depicts two kneeling figures engaged in the laborious process of collecting cochineal insects from a nopal cactus. This serves the dual purpose of connecting the dots between the labor behind the quilt and the object itself, and enticing the viewer to come closer, thereby encountering the individual stitches and marks of wear on the fabric that might otherwise be missed.

While “An Ecology of Quilts” is seemingly the first curatorial endeavor of its kind, a growing number of contemporary artists have been investigating the material histories and ecological implications of textile production and trade over the past decade. I was reminded several times throughout the exhibition of the work of Sonya Clark, whose fiber-based installations—such as Monumental, a large-scale, madder- and

tea-dyed linen version of the white dish towel waved in 1865 that signaled the Confederate army’s surrender—unravel narratives of race, gender, labor, and nationhood. Candice Lin’s 2016 exhibition A Body Reduced to Brilliant Colour at Gasworks, a low-tech installation incorporating cochineal, sugar, tea, and other commercially traded goods, was a material exploration of the ways in which colonialism and slavery have shaped our aesthetic tastes.

Ambitious in scope and original in framing, this exhibit leaves viewers haunted by the questions: at whose expense has quiltmaking been allowed to flourish? And how do we square a human craving for beauty with the violence often embedded in its pursuit?

“An Ecology of Quilts: The Natural History of American Textiles” remains on display through March 1, 2026, at the American Folk Art, Museum 2 Lincoln Square, 10023. Visit folkartmuseum.org for hours and ticket information.

Photos by Emma Fiona Jones.