The Great Potato: Chicago World’s Fair Requested Giant Long Island Spud

In the fall of 1890, Ferris Talmadge Sr., who owned a potato farm in the Springs, received a letter from the promoters of the upcoming Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. They heard of him, they wrote, and they wanted to ask if he would, for a fee, grow the world’s biggest potato so it could be brought to Chicago and be put on view for the visitors there. Of course, Talmadge said yes. The fee would be big, though.

The following spring, Talmadge took a special cutting out to one corner of his farm and planted it on a low hill there. This was a considerable distance from his regular potato field. He would need lots of room for the big potato to grow.

During that summer of 1891, Talmadge had his farmhands rake a special kind of potato food he’d created into the soil. When the potato plant peeped up out of the ground in late April, he had a special kind of water ready for it, too.

The potato grew all through the summer of 1891, and Talmadge could see that the height of the hill was rising and he was pleased. But that fall, when he dug up all the rest of his potatoes he left this one in. To grow really big, he knew, he would need another growing season.

The promoters of the Chicago World’s Fair wrote him that autumn and asked him how things were going, and he said right on schedule. He expected to have it ready to harvest in the autumn of 1892. It would be ready in plenty of time for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, scheduled to open in April.

The next autumn, however, Talmadge felt the potato still wasn’t quite ready. It had been a hot summer. It just wasn’t ripe.

When the promoters wrote him that fall to arrange for shipping, he wrote back saying he wanted to leave the potato in the ground for one more winter. He would have it out at the end of March, at the beginning of the thaw. He knew this was cutting things close and he knew the promoters would be panicky about this, but he asked them to trust him. They said they would.

In late March of 1893, on a warm Monday morning, Talmadge climbed the big hill at the edge of his field, kicked at the ground and said his potato was ready.

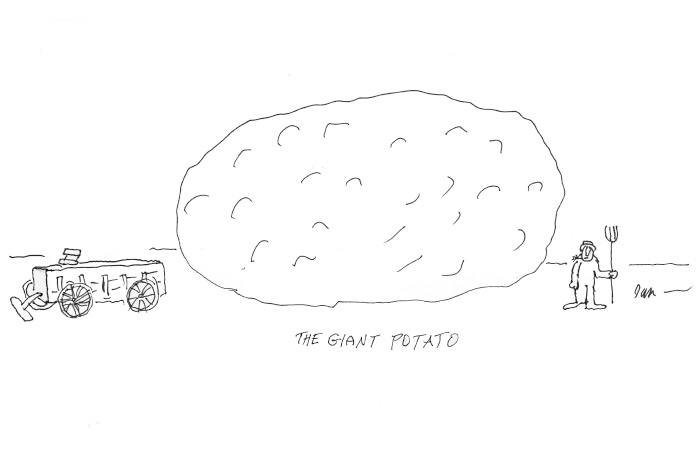

He brought his six farmhands over with picks and shovels, and they labored for an entire day just to uncover the top of the potato. It was big, all right. From end to end, it measured more than 33 feet.

The workmen dug for the rest of the week and into the next. By the following Thursday, they had dug all around the big potato and it was completely visible there, sitting deep in a big hole. Half the townspeople of the Springs came out that Thursday afternoon to have a look.

How was Talmadge going to get that potato out of there, the people wanted to know? It was going to be a problem. Talmadge put a thick rope around the potato and tied it to a team of six horses. But the horses pulled and pulled and the potato would not move. They pulled all day until they were bathed in sweat. Nothing happened.

That night, Talmadge had a brainstorm. In the morning, he asked that the strongest wagon in the village be brought up to the big hole and then pushed down into it, next to the potato. Then he got a team of 12 horses and tied ropes from them to the potato, and after 20 minutes of mighty pulling they had raised the potato up about seven feet, just high enough for Talmadge’s men to push the wagon under one side of it.

The wagon creaked and groaned with this added weight, but it held. Talmadge brought over a second wagon and placed it next to the hole, but on the other side. The farmhands and the horses then pulled and pulled and lifted the other side of the potato up seven feet, high enough for that second wagon to be shoved down into the hole and under it.

The two wagons holding up the potato were then tied together in tandem with heavy ropes. This was a dangerous business, with the farmhands under this enormous weight that might give way at any moment. But in the end, the effort was successful. After that, everybody went home for the night, exhausted.

The next morning, the men used picks and shovels to dig an incline up one side of the hole so the two wagons could be hauled out. The farmhands got behind the back, the team of 12 horses tugged on the ropes tied to the front and they pulled that potato up the side and out into the pasture and, by evening and with great effort, down to the rocky beach there at the end of Fireplace Road.

It took about 10 days for Talmadge to come to the conclusion that there wasn’t a boat owner on eastern Long Island willing to haul that potato to Chicago. Talmadge wrote the promoters a letter telling them he had the potato on the beach but that was all. The promoters said they would take possession right there.

Six days later, a freight boat from Manhattan arrived in the bay just off Fireplace and dropped anchor. It was towing a barge, which was floated to a sandbar near shore. Ropes were secured from a winch on the barge to the wagons and potato and the lot was cranked out through the surf and onto the barge where, lo and behold, it was found that the cargo floated!

The freight boat towed the barge away. But just 200 yards out, the wind came up, the surf began to chop, and the freight boat’s captain ordered the barge returned to the shore. It was too dangerous to proceed. The potato and its two wagons were taken off. And there they remained, on the beach but now the property of the promoters of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Local folks were very depressed about this situation. But two days later, Talmadge received a telegram. The promoters had wonderful news. Due to other delays, the fair opening had been postponed to June 15. So now there was much more time.

“As you may know,” the letter said, “more than a dozen railroads come into Chicago from around the country. The fair is alongside one of them. We have contacted Austin Corbin, the owner of the Pennsylvania and Long Island railroads, and he has agreed to extend the Long Island Rail Road, which currently ends in Southampton 20 miles from you, all the way to East Hampton, just three miles from you, by June 1. Can your horse team haul the potato to downtown East Hampton by June 5? You’ll see the new tracks. We’ll have a freight car there big enough to handle the situation. Just 72 hours later, we’ll have the potato. We are very excited about this.”

Again, Talmadge said yes. And what a day that was. On June 3, 1893, the whole town escorted that potato on its two wagons to where the train tracks now ended at Newtown Lane. The high school band played. President Grover Cleveland came from Washington. And at sunset, an enormous steam locomotive puffing black smoke arrived to haul that potato off heading west—the first train ever out of our town.

To be honest, nobody ever heard of the potato after that. And Talmadge never revealed what the promoters had paid him to grow this giant potato. But for years afterward, every March, Talmadge would hand out big bonuses to his farmhands. The money came, he said, from the annual check he was getting from Chicago. It was certainly quite a windfall for this community.