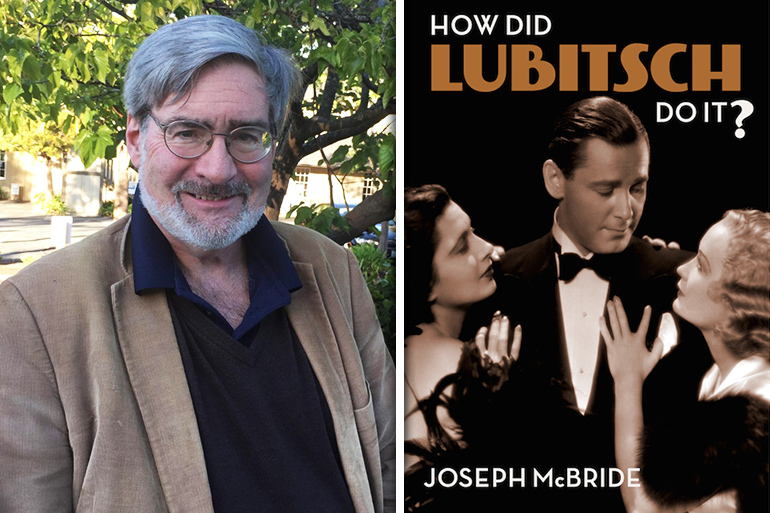

Danny Peary Talks to 'How Did Lubitsch Do It?' Author Joseph McBride Part II

In case you missed Part I of my conversation with renowned film critic/historian Joseph McBride about his marvelous new book, How Did Lubitsch Do It? (Columbia University Press), you can read it here:

Danny Peary Talks to ‘How Did Lubitsch Do It?’ Author Joseph McBride, Part I

In my intro to Part I, I wrote: How Did Lubitsch Do It?, a much-needed critical appraisal of one of the most important directors in cinema history, Ernst Lubitsch. McBride, who even traveled to Germany to watch the silent films he made there before coming to America, provides a brilliant shine to his fading star.

Definitely take a look at the book’s website: howdidlubitschdoit.com

This book had such appeal to me because when we both were at the University of Wisconsin in the 1960s, I was first introduced to several Lubitsch films by McBride when he ran the Wisconsin Film Society. So I was delighted that we could have the following conversation about a bigger-than-life figure who deserves such a big tribute.” Here is Part II, the conclusion of our back-and-forth.

Danny Peary: My sense is that you decided to write a book on Ernst Lubitsch primarily to bring him back into the public eye at a time you are frustrated by current Hollywood romantic comedies. And as an excuse to seek out his hard-to-find films. How much of the real world can we see in Ernst Lubitsch’s movie world?

Joseph McBride: He wasn’t that interested in the “real world.” He famously declared, “I’ve been to Paris, France, and I’ve been to Paris, Paramount. I think I prefer Paris, Paramount.” But it is a curious fact, as a European critic once observed, that Lubitsch’s films often coincide with major political upheavals. He also made what another European critic has described as a political trilogy with Trouble in Paradise (about the Depression and capitalism), Ninotchka (about Stalinism vs. capitalism), and To Be or Not to Be (about fascism). As a Jewish artist during World War II— one who even was held up by the Nazis as a symbol of how they hated Jews—he felt driven to confront the world outside the studio in all its ugliness in To Be or Not to Be. But it was characteristic that he did so through black comedy and by focusing on the artificial world of theater people, the world he knew and loved best. They represent humanity to him.

DP: One thing that is absent from his movies—or my memory of them—is children.

JM: He has youthful apprentice figures in his German films, including himself in his shop comedies and the raucous kid in The Doll, and Pepi (played by William Tracy) in The Shop Around the Corner is in that direct lineage. But Pepi is no child, and little children are scarcely seen in Lubitsch. He has schoolhouse scenes in some of his early comedies. And Henry is shown at early stages of life in Heaven Can Wait. Ossi Oswalda is a teenager in some of the farces she did with Lubitsch, including I Don’t Want to Be a Man. But children, especially little children, generally were not sophisticated enough to engage his interest as characters.

DP: Also, other than the Nazis in To Be or Not to Be, are there significant villains in his work?

JM: Lubitsch is essentially a comedy director, and Aristotle notes in his Poetics that comedy deals with human flaws. Most people in Lubitsch have human flaws but can’t be called villainous. Even Satan is charming in Heaven Can Wait, and Lubitsch plays suave or mischievous devil figures in a couple of silent films. The speech Lionel Barrymore’s German doctor gives in The Man I Killed attacking himself and his fellow fathers who sent their sons to war is quite scathing, though. And one can call the Pharaoh (played by Emil Jannings) villainous in The Wife of Pharaoh, though he’s also pathetic; his Egyptian villain in The Eyes of Mummy Ma is rather ludicrous, showing that Lubitsch wasn’t attuned to that kind of character excess.

DP: Indeed, other than the actor characters and the young Polish aviator (Robert Stack) in To Be or Not to Be, are there any significant heroes?

JM: I suppose that’s a good point, that the concept of heroism, like the concept of villainy, is too extreme for Lubitsch in general, other than in the context of world wars. Benny’s Josef Tura becomes a reluctant hero in To Be Or Not to Be, as does his wife, Maria (Carole Lombard), who is a more determined member of the resistance. But those are rare circumstances.

DP: Are there winners and losers in his movies?

JM: Winners and losers in his work are often interchangeable. He exemplifies what G.K. Chesterton declared, that if you love someone, you love him for his flaws as well as for his virtues.

DP: You write that Lubitsch wanted to explore the nature of love triangles. But wasn’t it less his exploring than presenting his firmly-established sympathetic view on the subject?

JM: I disagree — he explores all the nuances and complexities of love triangles of various kinds and works many variations on that theme. His films often revolve around the problems and joys of triangles and how those questions are interrelated and resolved. Lubitsch usually avoids the common filmmaking dodge of loading the dice by making one woman or one man in the triangle less attractive and likable than the other, so the films complicate our reactions by making it as hard for us to choose between them as it is for the characters themselves. I am thinking especially of Lubitsch at the peak of his artistry in Trouble in Paradise, in which Herbert Marshall’s difficulty in having to choose between Miriam Hopkins and Kay Francis mirrors ours. But perhaps that is one reason Lubitsch then made Design for Living, so Hopkins doesn’t have to choose between Gary Cooper and Fredric March in the end.

DP: You write that Lubitsch’s style radically changed after 1934 because of his conflict with censors and the strict enforcement of the Hays Office Code. If there had been such a stringent Code when Lubitsch arrived in Hollywood, how would that have affected his early films and his legacy? And what if there had never been a Code implemented?

JM: Lubitsch was fascinated by sexual intrigue and what it reveals about human nature. He spent much of his career outwitting the censors. It was something of a game to him but also necessary to his survival, since they were trying to suppress the subject he found most compelling. It was essential to his truly adult approach to sexuality. As James Harvey writes of Lubitsch, “Like nearly all the working filmmakers in the Hollywood of the time, he played the game,” but Lubitsch was special because he “made movies about playing the game.”

He was already developing his characteristically oblique style of humor in dealing with sexuality and social transgressions in his German films, but when he came to America, bringing his continental approach with him, his celebrated elliptical, allusive style of storytelling developed largely in response to his need to circumvent the censors. Harvey observes that a principal reason Lubitsch was so highly regarded by other directors in his time was that he was so clever in getting “his dirty jokes” past the censors. That made Lubitsch “a model and an ideal” for other filmmakers, “for it wasn’t just mockery and dirty jokes that he got away with: it was intelligence itself, in a system that tended to empower stupidity.”

“Playing the game” with audiences and engaging their mature intelligence became his distinctive style, his way of seeing the world. François Truffaut wrote in his famous 1968 essay “Lubitsch Was a Prince,” “The essential consideration here is never to treat the subject directly. So, if we are kept outside the closed doors of the bedroom when everything is happening inside, stay at the office when everything is going on in the living room, remain in the salon when the action’s on the stairway, or in the telephone booth when it’s happening in the wine cellar, it’s because Lubitsch has racked his brain during six weeks of writing so that the spectators can work out the plot along with him as they watch the film…[Lubitsch] has already examined all the previous solutions as to offer one that’s never been used before—an unthinkable, bizarre, exquisite and disorienting solution. There are outbursts of laughter as we discover the ‘Lubitsch solution’—our laughter is uncontrollable.”

DP: Was it essential for his screenwriters, particularly Samson Raphaelson and Hans Kräly, to agree with his unorthodox view of marriage and adultery, or did they simply write from his perspective?

JM: Lubitsch had fertile and close collaborations with his writers, but he was so dominant that the three screenwriters of Ninotchka (Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder, and Walter Reisch) actually petitioned the Screen Writers Guild to let Lubitsch share credit with them. I’ve never heard of that happening before or since, and the Guild wouldn’t allow it, but Wilder said, “If the truth were known, he was the best writer that ever lived. Most of the ‘Lubitsch touches’ came from him.” Melchior Lengyel, who supplied the material for four films Lubitsch directed, said, “Writing for Lubitsch is just kibitzing.”

Raphaelson, who was witty in his own right and a strong constructionist, admitted in later years that he didn’t fully understand how good his work with Lubitsch actually was; he had the delusion that his plays were better, but it is his brilliant screenplays for Lubitsch that endured, somewhat to his chagrin. So the writers more or less had to be in harmony with Lubitsch’s view of the world and seem to have accommodated to it without undue strain. Ironically, Hans Kräly, who wrote most of Lubitsch’s work in both Germany and Hollywood from 1915 through 1929, broke up with him because he was cheating with Lubitsch’s first wife. It was Lubitsch’s one brush with scandal, and though it was devastating for him and led to Kräly’s career collapsing, it was like a real-life Lubitsch tragicomedy.

DP: Lubitsch made too many classics for us discuss any in proper depth now, but let’s touch on a few that you write extensively about in your book. Considering that it came out in 1924, was The Marriage Circle his most daring film?

JM: I would call that his most influential film, since it in effect created the romantic comedy genre in Hollywood and was regarded as a career-changing lesson by so many major and disparate filmmakers. But I’d say Lubitsch’s most daring film, by far, was To Be or Not to Be, which caused a firestorm of outrage from reviewers (such as the perennially clueless Bosley Crowther of The New York Times) at the time of its release in early 1942. It was an audacious film to make in wartime, especially since it was in production even before Pearl Harbor. Reviewers and some (but not all) audience members didn’t know how to get their bearings in this still-unexplored realm of black comedy.

We love the film today partly because we’ve become accustomed to black comedy in the post-Dr. Strangelove modern world, with full knowledge of all history’s horrors, and because, with distance, we can value the truth as well as the audacity of what Lubitsch was doing in using humor to attack the Nazis in the time of what we now call the Holocaust. Lubitsch knew his fellow Jews were the victims of mass murder and used the best weapon he had to call the world’s attention to the dimensions of the Nazi menace to humanity.

DP: You quote Molly Haskell writing that Trouble in Paradise has “never gotten the attention that it deserves, because it is really about sensuality and morality.” But don’t you think that is precisely why it gets the attention it does?

JM: The fact that Trouble in Paradise has not received the attention it deserves is partly due to the fact that after the Code was enforced in 1934, the film was forbidden to be reissued, and it also didn’t play on television for a long time either. I finally saw it only when it was released on 16mm in the late 1960s. Most people still haven’t caught up with it. I would agree that those of us who love the film do so partly because it is “really about sensuality and morality.”

DP: We may feel Herbert Marshall is sacrificing his own happiness to stay with fellow-thief Miriam Hopkins, who needs him, at the end of Trouble in Paradise, but do you think Lubitsch believed he would be better off in the long run if he settled down with Kay Francis? I don’t.

JM: Lubitsch clearly shows that would be impossible for both Marshall and Francis if they tried to remain together, since he would go to jail and she would be ruined by the scandal. The sadness underlying the ending—so perfectly captured in their poignant farewell scene and Francis’s gracious acceptance of his departure—is summed up by the fact that the characters “just obeyed the dictates of society” (to borrow a line used in a somewhat different way in Lubitsch’s 1930 musical Monte Carlo). But we also feel that as alluring as Francis is, Marshall is better suited to a partnership in crime with Hopkins, whom he loves even more deeply, so the ending is exhilarating, if also bittersweet.

DP: Do you see a link between the endings of Trouble in Paradise and Casablanca, with Ingrid Bergman doing essentially what Herbert Marshall does?

JM: I have a theory that the love stories we value most in cinema—including these—have unhappy endings or endings with mixed emotions. Think also of Gone With the Wind, E.T. and Titanic. We value most what we have lost. None of these films would be better if the couple that separates would walk off into the sunset together, and we wouldn’t care for them as much, because they would seem false. Ironically, Hollywood has rarely understood that audiences can be so deeply moved by unhappy endings, so they usually twist stories into happy endings. This is partly a product of what Frank Capra told the U.S. government while serving as a propagandist during the Cold War: “The happy ending is a national characteristic.”

DP: Design for Living was adapted from Noël Coward’s play, but if there hadn’t been censorship in the movies do you think Lubitsch and screenwriter Ben Hecht might have done away with Hopkins insisting her relationships with Cooper and March be platonic and made it clear that she’s having sex with both?

JM: That bit about her proclaiming they will have a “gentleman’s agreement” not to have sex is clearly a wink to the audience — as she later admits, “I’m no gentleman.” We get that she’s having sex with both of them, though apparently not simultaneously (as even Lubitsch has his limits in kinkiness). Coward’s play has gay overtones, and it is also overtly anti-female. Lubitsch loves women. Hecht created a sort of love story between two men with Charles MacArthur in their play The Front Page, but it was not homosexual per se, more of the prototype of the buddy-buddy movie, even though that has its homosexual undertones. Lubitsch doesn’t seem much interested in homosexuality other than flirting with it in I Don’t Want to Be a Man, which takes an open, tolerant, mischievous attitude toward the subject. He was just more interested in male-female relations.

DP: Do you think the ending of Design for Living is a sellout?

JM: Hardly—it’s the opposite—the three of them are shown in the last shot with her arms around the two men going off in a taxicab to more sexual adventures. Though the film shows that pulling off a menage à trois is challenging due to jealousy and other such human complications, he’s all for the attempt.

DP: I have never seen his 1932 antiwar film, The Man I Killed. How important was it to Lubitsch and how important is it for us?

JM: Even though he fortunately was a noncombatant in the Great War because he was a Russian citizen, Lubitsch had vivid memories of how terrible it was, and he wanted to share them as well as to warn the audience—quite explicitly and accurately—that it could happen again with Germany. But as sometimes happens when Lubitsch tackled heavy drama, the film is very heavy-handed, and the lead performance of Phillips Holmes today seems ridiculously overwrought. It must be noted that critics raved about the film and Holmes at the time, but the film was a huge commercial flop, even after Paramount desperately retitled it Broken Lullaby. The best parts of the film, ironically, are when it incongruously turns into a dark sort of romantic comedy. The French “remake,” Frantz (2016), is a much better film, although director François Ozon admitted he had never heard of the Lubitsch film until after he started writing his script adapting the original 1925 play by Maurice Rostand, The Man I Killed. That’s sadly typical of the ignorance toward film history even among people in the film industry.

DP: Is The Shop Around the Corner, Lubitsch’s rare movie in which adultery is contemptible, his most universally liked movie?

JM: It seems to be his most popular today. People find it heartwarming, which it is in a way, but it reminds me somewhat of It’s a Wonderful Life, which is quite a dark film in actuality. I admire Shop but find it rather chilly as well, since the lead characters played by James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan snipe at each other until the end, not knowing they are secretly in love with each other. This keeps the film from falling into a morass of sentimentality and schmalz, as does its nearly tragic adultery theme involving Frank Morgan’s shop owner and his offscreen wife, whom Lubitsch characteristically called “almost the most important character in the picture.” And Shop is a breathtaking tour de force of how to direct a film largely in an enclosed space, and the ensemble work and dialogue are wonderful. You only have to compare it with the play (Parfumerie by Miklós László) or the two mediocre remakes (In the Good Old Summertime and You’ve Got Mail) to see how brilliant the Lubitsch version is.

DP: Heaven Can Wait is the rare Lubitsch film in which his characters don’t take turns successfully deceiving one another into believing they’re someone they’re not. Do you think it is his most ambitious film thematically?

JM: I wouldn’t say that, although it is a masterful piece of narrative by Lubitsch and Raphaelson (based on the Hungarian play Birthday by Laszlo Bus-Feketé), telling the story of a man’s life through his relationships with the women in his life, covering long stretches of time and having fun with changing social mores in America. I consider Don Ameche’s death scene the greatest death scene in the history of movies. That lovely scene is both a nostalgic tour of Lubitsch’s life and work and perhaps his supreme example of expressive ellipsis.

DP: Do you think he liked the philandering husband played by Don Ameche? Did he see him as his alter ego?

JM: Lubitsch loves the guy. He forgives him everything—maybe too much—but then his wife (played by Gene Tierney) accepts his philandering, and Molly Haskell says that after initially thinking the film is sexist because it embraces the double standard, she gradually came to accept the film as an unconventional view of a happy marriage. That’s how Lubitsch intended it, since he took a continental view of adultery. And he coaxed a charming performance out of the gentle, soft-spoken Ameche, who plays against the type of a suave philandering cad to the point at which we wonder how successful he really is at that game. But Lubitsch’s true alter ego in films is Felix Bressart, the funny and deeply moving Jewish German refugee character actor who is the heart and conscience of The Shop Around the Corner, Ninotchka, and To Be or Not to Be.

DP: It’s hard to believe because of his tremendous output, but Lubitsch was only 55 when his heart gave out.

JM: As Truffaut movingly put it, Lubitsch “worked like a dog, bled himself white, died 20 years too early” by wracking his brain to think of plot and character turns and to entertain us. (Truffaut also died twenty years too early.)

DP: The obvious question is: Did Lubitsch die before he became increasingly passé or did his last completed film, the appealing 1946 comedy Cluny Brown, indicate that he had many fertile years ahead?

JM: As charming as Cluny Brown is, it seems somewhat quaint and old-fashioned even for its time, which is not a flaw but a sign that the world was moving on. I am not sure Lubitsch would have had it in him to reinvent himself again in the more hard-edged postwar era in filmmaking. As Sarris observed, “The world he celebrated had died—even before he did—everywhere except in his own memory.” His retreat after that to his tired throwback to his earlier musicals, That Lady in Ermine, does not indicate he had the desire to move into the grittier kinds of films being made by Wilder and other leading younger directors of that period. Wilder observed in 1975, “Ernst Lubitsch, who could do more with a closed door than most of today’s directors can do with an open fly, would have had big problems in this market.” Unfortunately, that’s even more true today. Lubitsch would not have been at home in the generally coarse world of modern romantic comedy.

DP: Which film do you think made Lubitsch the most proud?

JM: In 1947, shortly before he died, Lubitsch wrote an expansive letter to Herman G. Weinberg stating that his best work was in Trouble in Paradise, Ninotchka, and The Shop Around the Corner. He also expressed satisfaction with The Oyster Princess, The Doll, Kohlhiesel’s Daughters, The Marriage Circle, Kiss Me Again, Lady Windermere’s Fan, The Patriot, and Heaven Can Wait, as well as a few others. He reserved special mention for To Be or Not to Be, a film he described as one that “in my opinion has been unjustly attacked. This picture never made fun of Poles, it only satirized actors and the Nazi spirit and the foul Nazi humor. Despite being farcical, it was a truer picture of Nazism than was shown in most novels, magazine stories, and pictures which dealt with the same subject.”

DP: Lubitsch made so many splendid films, so what do you think was the major cause of his few disappointing ones?

JM: Being overly solemn, a trap he sometimes fell into because he wanted to be taken more seriously or had something to get off his chest, when his true gift was for comedy-drama.

DP: You write that Lubitsch’s “ability to change and grow artistically is one of the reasons he endured as a top director for decades.” Was he at times satisfied to adapt to the times or was he always trying to be a groundbreaker?

JM: He did the kinds of films he loved to do, and had considerable autonomy, but he still had to respond to changes in public taste and to the tightening of censorship. Truffaut observed that the audience is an essential element in a Lubitsch film, and Lubitsch was a popular artist who would never have ignored his audience. So when the public tired of spectacles or musicals set in mythical kingdoms, he found other forms in which to express his feelings and obsessions. He wasn’t pandering but trying to be responsive and keep his audience. One of the times he faltered badly was when he ventured into screwball comedy with Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife; screwball is a type of comedy that deals with violence and loathing between the sexes, and this film, which for the most part is painfully unfunny, showed that was not his forte.

DP: Why do you think his films have been so hard to remake, including by himself? Even a film that was inspired by Lubitsch, The Man Who Loved Women was, in my opinion, one of Truffaut’s least likable films.

JM: I find The Man Who Loved Women disturbing and candidly autobiographical and think Truffaut fully intended it that way. While he was writing the script, he showed me his typewriter at the Beverly Hills Hotel where he was working under a framed photograph of Lubitsch. Until I was writing my Lubitsch book, I missed that glaring signal that The Man Who Loved Women is Truffaut’s version of Heaven Can Wait. One reason I find the Lubitsch influence more salutary to Truffaut’s work than it is to directors who imitate him more slavishly is that Truffaut manages to incorporate a Lubitschean sensibility within his own rather than just trying to copy it, which usually results in clumsy second-rate filmmaking. Even Wilder, master that he was, admitted in a 1967 tribute to his master, “Oh, if we were lucky, we sometimes managed a few feet of film here and there in our work that momentarily sparkled like Lubitsch. Like Lubitsch, not real Lubitsch. His art is lost. That most elegant of screen magicians took his secret with him.” But we still have the films.

DP: If you got to ask Lubitsch two questions, what would they be?

JM: That’s a challenging question! I would say, “Could you explain your feelings about your native Germany after 1933 and how you decided to forbid the speaking of German in your house after that?” And then I suppose I would ask, “What’s your next film? How do you see your future in Hollywood?”

DP: What is the most underrated aspect of Lubitsch’s filmmaking?

JM: How fundamentally serious his comedies are.

DP: What is the best way to see Lubitsch’s films without going broke?

JM: I had to spend my own money traveling around the world to see the films or get myself invited to be the curator of the Lubitsch retrospective at the Locarno (Switzerland) International Film Festival in 2010. A growing number of his films are now on DVD, more than when I started my research, but that can be expensive for people as well. I guess you just have to care enough to seek out the very best. I hoped that by writing my book I would encourage home video companies and others to make more Lubitsch films more easily available. Owning physical media remains important, since streaming companies come and go—FilmStruck had fourteen Lubitsch films running before it folded, and so far the new Criterion Channel has only two. It’s a struggle, but that’s the nature of film history—we have to seek out and discover films for ourselves and not expect them to drop into our laps.

DP: How can people purchase your book?

JM: Through amazon.com is the easiest, or through the Columbia University Press website, cup.columbia.edu.

DP: And what about your even new book Frankly: Unmasking Frank Capra?

JM: It was published on March 22 by Hightower Press in Berkeley and is sold exclusively on Amazon.

If you missed Part I of this interview, read it here.

Danny Peary has published 25 books on film and sports, including Cult Movies,Jackie Robinson in Quotes, and his newest publication with Hana Ali, Ali on Ali: Why He Said What He Said When He Said It, about the origins of her father’s most famous quotes (Workman Publishing).