Block Island Lawsuit: Arguing the Word 'Scam'

My son David, now in his early 40s, is studying law. He’s begun his first year. Yesterday he called. They are studying case law. Cases are presented and the students discuss them.

“One of them is about you,” he said. “Your case is studied in law schools.”

Wow.

One remembers being sued for $1.1 million. It involved freedom of the press. There was a trial, a jury, and the works. It was about something I wrote.

The year was 1984. David was 3, his brother was in a baby carriage, and me, my wife and the kids were strolling on Main Street, Block Island, the big tourist island just off the coast of Montauk. I had started a newspaper on Block Island four years earlier. There’d never been a newspaper there. Now there was the Block Island Times, one of Dan’s Papers. It continues today as the paper of record. Although I no longer own it.

On Main Street that summer day, there were several young men with clipboards accosting tourists, telling them that they could get a free lobster dinner if they’d go with them to an office and listen to why they should buy timeshares in a motel on the Island. It piqued my interest.

The office turned out to be a booth in the motel’s dining room with dozens of other tourists and salesmen. We listened to the pitch. I had no interest in buying. And I thought it outrageous they were accosting people like that.

I looked at my watch. About a half an hour had gone by. And so my salesman gave up. In another office, a small one back on Main Street, he had us talk with the boss there who said we’d only been there a half hour and you had to be there 45 minutes to qualify for the lobster dinner.

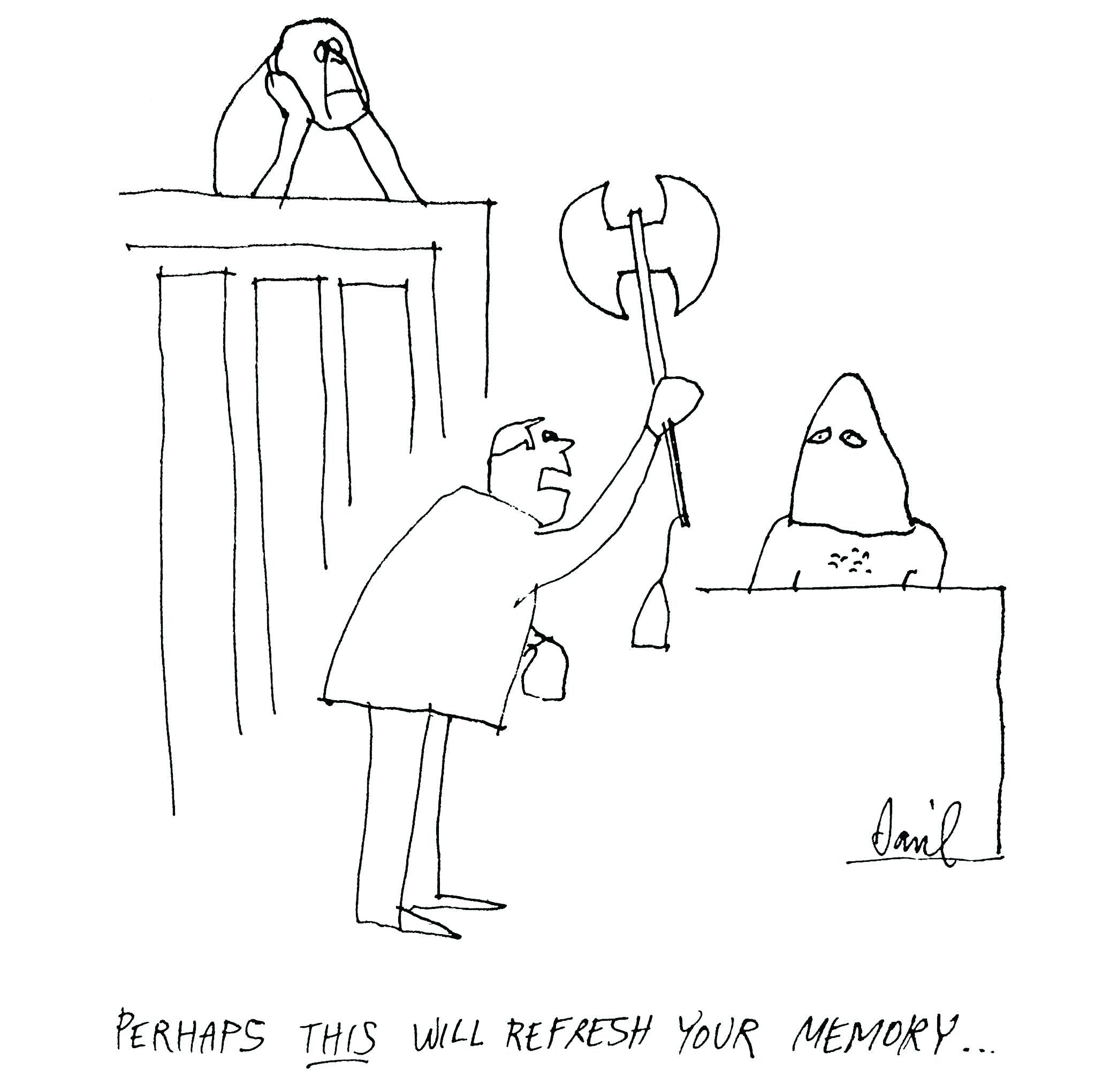

I wrote a story about this encounter and ran it on the front page in the Block Island Times. The headline was “Selling Time Shares on the Street.” And they sued me for libel.

The lynchpin of their claim involved the word “scam.” I hadn’t used it in the story. But when laying out that issue late at night in our Bridgehampton office where all that sort of work was done, my production manager, without my knowledge, used it. The story’s file name had been saved as “Scam.” And, at 2 a..m, after I left the office with only a few things left to be done, she added it. The story, spilling over onto a second page, needed a jumpline. On that second page, SCAM invited you to continue there.

I was caught up short when I saw it after it was printed, but there was nothing I could do. I thought this too shall pass. It didn’t.

The trial, in a federal courtroom, took place the following year. A professor from Brown University – this was in Providence, Rhode Island as Block Island is in Rhode Island – described the damage done to his client by my use of that word. The owner of the motel was running to be a town selectman on Block Island. He’d had to quit that. His business suffered.

I was on the stand for most of that day. My lawyer said just tell the truth, so I did. The word had been there by accident. But yes, I thought it was a scam.

The prosecution rested as the day ended. Our defense would begin the following morning. I spent the night tossing and turning in a Marriott. And at 8 a.m., a half hour before the judge would gavel the trial to order, I met my lawyer in a meeting room.

He told me that first thing, he would ask that the charges be dismissed. Defense lawyers always do that. It’s routine, and the judge would refuse it. He’d say get on with your defense. He also told me that just before our meeting the prosecution had told him they would settle if I paid $90,000. Would I agree to that? He recommended it. You never know what a jury is going to do. I told him all I’d done was publish an opinion. So, no. He shrugged.

“Okay,” he said. And off we went into the courtroom.

Everyone got in their places, the judge called the case to order, and my lawyer asked the case be dismissed. This is what the judge said. It’s rough. But it’s as I remember it.

“Before I rule,” he said, “I want to thank the jury for the time they have taken to attend to this matter. You’ve taken two days out of your schedules. It’s important that justice be served. But in this case, it’s over. I am dismissing the charge. And we are all going to go home.”

He then asked for the jury to listen to him as to why this was. And he spent the next 20 minutes lecturing them about on the one hand the rights of individuals to be compensated for slander but on the other, the rights of journalists to express their opinions. A judge has to decide, and he has to take into account the context of the situation and in this case, Rattiner had told the story as an encounter, a very credible one, and as a result, the reader would see it was the journalist’s opinion and he, the reader, should feel free to form his own. As for scam, accidental or not, it was clearly Rattiner’s opinion. And that’s allowed. Thank you again for your service.

Six months later, an appeals court upheld this decision.

I would like to talk a moment about the lawyer I hired. I knew Long Island lawyers, but none in Rhode Island. The owner of the Block Island Airline, Bill Bendokus, had told me the whole island was behind me and he would fly me free wherever I needed to go for hearings or depositions and he recommended this lawyer.

The lawyer was Joseph V. Cavanagh Jr. I recall our first meeting. I had an address. Taking a taxi to it from the airport, I noticed it was in the tallest building in the City of Providence. Inside, the elevator took me all the way up to the top where, it turned out, he had the corner office. There, he smiled and shook my hand grandly.

My goodness. How the hell had I been so lucky.

Law schools today discuss this case as one that expanded the rights of the press.

Just Google it: McCabe vs. Rattiner.