Son House: Famed Delta Blues Artists Lost Years on Long Island

The famed father of Delta Blues, Edward James “Son” House Jr., known by his stage name, Son House, has received a resurgence of interest among music historians — including his lesser-known time living on the North Fork.

As of January 2026, the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi, unveiled its new online interactive exhibit, “The River and the Road to the Blues,” detailing the lives of artists such as Son House and others he inspired in his famed home near Clarksdale. In Rochester, New York, Record Archive — the city’s biggest record store and private musical venue — will celebrate the historic connections of Son House’s resurgence in Rochester by hosting a Blues Night every Thursday for famed local Blues artists to perform Son House cover songs.

But what about celebrating Son House’s Long Island years? These so-called lost years followed his resurgence into a world-renowned musical career.

One of the most widely known myths about Delta Blues is that of Robert Johnson, who achieved national success with his hit song “Cross Road Blues.” Johnson, according to legend, sold his soul to the devil at the local crossroads to learn to play the guitar. But experts say that story was a marketing ploy — his real teacher was the local blues man.

“Robert Johnson never said the devil told him how to play guitar,” Shelly Ritter, director of the Delta Blues Museum, told Dan’s Papers. “It was a narrative that somebody invented to sell records. Son House taught Johnson to play the guitar.”

Ritter explained her rebuttal to this myth.

“He [Son House] always played the resonator guitar (steel guitar), and brought the bottleneck, slide-style of playing to the forefront,” Ritter said. “Charley Patton, Howlin’ Wolf- Everyone absorbed what everyone else was doing. We were rural then, and we are still rural. What happens two doors down is not filtered out, as it is in a city.”

However, despite his decades of local success, in the late 1940s Son House stopped performing and soon found himself on the migrant labor stream heading North.

“As farming became more mechanized and the boll weevil outbreak devastated crops, there were fewer and fewer jobs,” Ritter explained. “People had the illusion of better jobs and better lives up north, and by the 1940s and 1950s, they knew people who moved to northern cities that could show you the ropes.”

By the early to mid-’50s, Son House found himself at the Cutchogue labor camp, employed as a laborer for local Riverhead farms. His experience was anything but a better life.

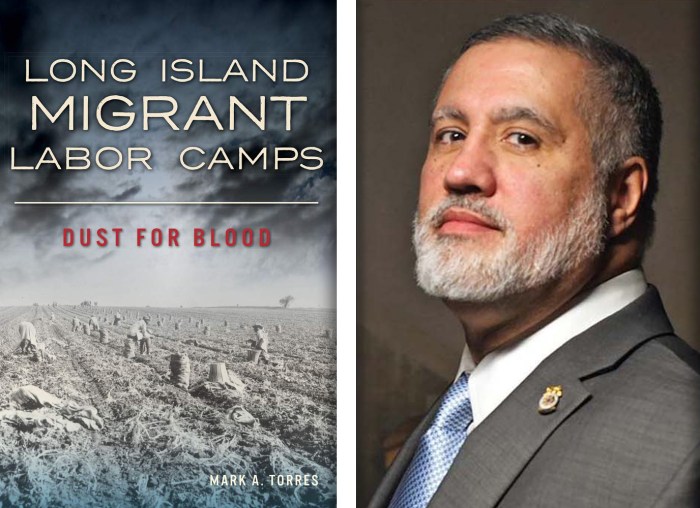

“These labor camps were makeshift structures where the impoverished migrant laborers lived in dangerous and cramped slum-like quarters that were not fit for human habitation,” Mark Torress, author of Long Island Migrant Labor Camps: Dust for Blood, said in an interview with Dan’s Papers. “Along with the physical dangers, the thousands of migrant workers who were lured to Long Island each year with promises of good wages and decent housing were instead economically exploited and found themselves mired in irrevocable debt and despair, burdened by physical and mental hardships, and left powerless to effect any change.

“One local advocate described the migratory labor camp system as a ‘20th-century form of slavery,’” he continued. “All of this took place less than 100 miles from New York City, in the backyard of one of the most scenic and affluent counties in the United States. It is difficult to provide all the time and detail he spent there because the life of a migrant farmworker was such a transient lifestyle.”

It is documented that Son House had a brush with local law enforcement and experienced violence at the camp firsthand, motivating him to leave Cutchogue. During this period, he revived his career in Rochester, New York, securing a recording deal with Columbia Records in 1965 for what is known as his “Father of the Delta Blues Sessions.” The most featured songs that defined his new wave of success were “Death Letter” and “Grinn In Your Face.”

What remains unclear is whether his newer songs were inspired by his time in the Delta or reflect his brief time on Long Island, which could make him a candidate for induction into the Long Island Music & Entertainment Hall of Fame.

Experts with the Stony Brook-based organization say they are considering it.

“We talked about the possibility of inducting him [Son House] into the Long Island Music & Entertainment Hall of Fame,” said Kerry Kearney, Blue, artist and researcher with the Long Island Music Hall of Fame. “When the director asked whether Son House was big in the blues world, I told them he is one of the kings, and that if he were here [on Long Island], it would be a big find. Having him in the Hall of Fame will be a big honor. We are still in the talking stage and researching his Long Island connection.”